We have all felt shame at some point. It is integral to our learning, yet it can block it too. Zoe Cohen considers shame within coaching and supervision and why it matters so much

Shame is a universally experienced human emotion and therefore, by definition, must be present in the field in our coaching and supervision. Yet there is little written about shame in coaching and even less about it in coach supervision.

My fascination with this topic and its inherent connection to learning led me to search the wider psychotherapy and counselling literature, and to conduct some research of my own with coach supervisors.

Below is the story that emerged for me.

What is shame?

Shame is a “feeling of humiliation or distress caused by the consciousness of wrong or foolish behaviour” (Soanes & Stevenson, 2008). As adults, we might experience shame in a number of ways, including mortification, ridicule, contempt, humiliation, helplessness, powerlessness, inadequacy and incompetence.

Shame is everywhere and often originates from early family and school experiences

Shame is described as far back as biblical times: in the Genesis story it included negative self-evaluation, excessive self-focus, hiding and blaming.

Shame has evolutionary and neurological roots in negative parental reactions to young children’s risky adventuring. Cozolino (2013) writes “what began as a survival strategy to protect our young has unfortunately become part of the biological infrastructure of later evolving psychological processes related to attachment, safety and self-worth”.

The question, ‘am I safe?’ has become interwoven with the question, ‘am I lovable?’

Brown (2012) describes shame as “the fear of disconnection”. She describes 12 “shame categories” emerging from her research:

- Appearance and body image

- Money and work

- Motherhood/fatherhood

- Family

- Parenting

- Mental and physical health

- Addiction

- Sex

- Ageing

- Religion

- Surviving trauma

- Being stereotyped or labelled

So there’s potential for shame on a daily basis in our adult lives. And therefore in our coaching practice.

Most psychological research has focused on the early parent-child relationship as the primary source of shame, with each person’s experience of shame reflecting their “differing developmental pathways unique to each individual”

(Hahn, 2001).

School settings are considered the second most common source of shame for children. For example, Shelton (2002) explored how the perceptions and beliefs that children form as a result of school failures carry into adulthood and impact adult learning.

In my words, we each develop our own unique “shame script”.

Shame is integral to learning and yet can be a block to it

Learning inherently jeopardises self-esteem. To learn, we must admit, even if only retrospectively, that we don’t know everything. For some, admitting this vulnerability is too risky or painful – or both. So shame, or fear of it, may prevent us from being open to learning.

Educational processes are often shame-based and involve a right/wrong dynamic. The presence of shame can itself be a blocker to deep learning – indeed, neurologically, the stress created by shame inhibits the neuroplasticity that underlies new learning (Cozolino, 2013).

Supervision is inherently a shame-prone or shame-risky system

I believe that both coaching and supervision are fundamentally about learning; therefore shame is an ever-present risk. Potential feelings of conscious incompetence, along with the evaluation and exposure inherent in supervision, have a significant potential to generate shame among supervisees.

The explicit ‘normative’ role of supervision involves a risk of shaming one’s supervisee, albeit unintentionally.

Supervisees commonly experience shame in supervision

I found a general consensus in the therapy literature that supervisees typically experience shame in supervision.

In my own research using a questionnaire distributed at the 4th International Conference on Coaching Supervision in 2014, all respondents (15) reported having experienced moments of shame in supervision as supervisees. These were influenced by a range of factors, all coalescing around three core themes: the fear or experience of judgement by self or others, exposure and loss of contact.

- Things I did that should not be done

- Not wanting my supervisor to see that part of me

Why might this matter for clients?

Does all this potential or actual shame in coaching and supervision matter? Does it make a difference ultimately to clients and coaches? A number of authors have noted that therapist shame can significantly influence the process and outcome of psychotherapy (Ladany & Kulp, 2011). Hahn (2004) writes about psychotherapists working with individual clients who harbour a considerable amount of shame. They experience “negative therapeutic reactions”, ie, they seem to resist recovery.

This can also cause strong countertransference reactions of shame in therapists.

Shame can certainly influence which cases or issues supervisees bring to supervision. A number of authors highlight the selective reporting of techniques, and of whole cases. Webb (2000) asks: “Are clients getting the best kind of therapeutic intervention where their counsellors struggle to use supervision to look at the most difficult aspects of their work?”

Surely the same question could arise for coaches?

Half of the respondents in my own research had had an issue in their practice that evoked a sense of shame or embarrassment, which they had not taken to supervision.

- Where I haven’t been able to discuss it, I believe it hampers me as I bring only my own lens to attempting to resolve it

- It stops me learning because I hide

- When I feel shame I go young, and disappear and don’t learn

The literature is almost wholly negative about shame and its impact and yet when shame is discovered and explored effectively by the supervisor and supervisee it can enhance both the therapy and supervision (Talbot, 1995).

My own first-person inquiry supports the transformative potential of consciously, purposefully, taking shame-prone material to supervision. As supervisees, several of my respondents described a positive impact on learning:

- Where I have been able to discuss the shame it has moved me forward, improved my empathy and capacity to ‘hold’ others

- It enhanced learning, because it made me very aware of the situation, the content, my reactions and the reactions of the supervisor

- When I own it [the shame], it can be transformative

As supervisors, all agreed there were implications of supervisees not bringing shame-prone issues to supervision, for example:

- They will make themselves small and hide behind themselves so that neither they nor their clients will thrive

- Stress, shallow learning; they could carry the shame into other coaching situations as it’s unresolved

- Opportunities for learning are lost. Opportunities for more effective work on their part with their coachees are lost. Opportunities for a deeper relationship (and thus deeper insight) are lost

- Diminished performance; increased stress and potential health issues; inhibiting their openness with others and their ability to be empathetic

And yet shame isn’t necessarily voiced or effectively worked with.

So shame is human and universal, commonly experienced in supervision and can make a difference to the end users of the intervention as well as the therapists/coaches… and yet writers indicate that shame is seldom addressed (Hahn, 2001; (Anderson-Nathe, 2008). Clients don’t tend to disclose it and practitioners don’t often address it.

From my own research, respondents described a spectrum in their supervisors’ awareness and ability to work with shame sensitively and effectively.

From:

She noticed my feelings and helped me explore them. Her choice to also make me look from the perspective of the societal, cultural context was very effective. It made my problem a more general one. It helped me to notice it in others as well

To:

Not at all, she didn’t spot it

And:

He did not consider shame as a pain point for the supervisee because he was not careful with the sensitivity and sensibility of the people

As supervisors’ respondents themselves have noticed, shame is in the field, often through voice and non-verbal changes including: body language, colouring up, tone of voice, avoidance of eye contact, hesitance in bringing issues and staying at content level.

Many agreed their supervisees could take more risks with what they brought to supervision. However, not all felt fully comfortable about working with shame with their supervisee, and some felt their supervisor training had not equipped them very well.

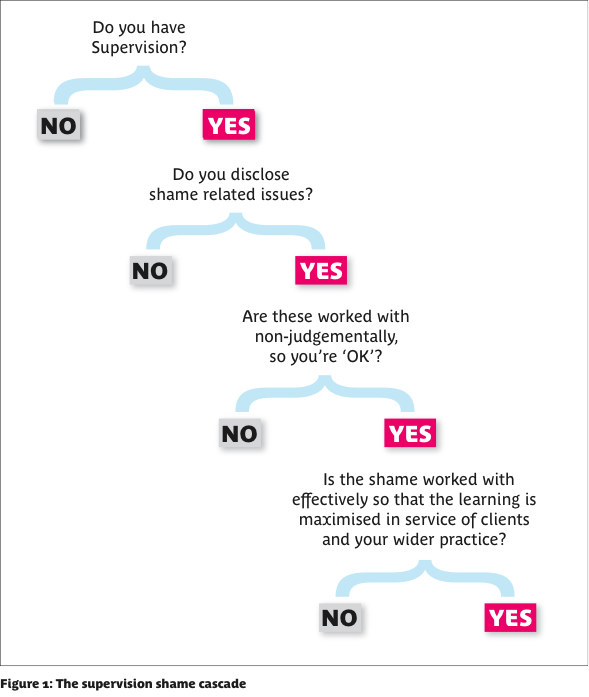

With coach supervision a developing area, and by no means all coaches undertaking supervision compared with the requirement in clinical therapies, this would suggest a large quantum of unvoiced and potentially unaddressed shame in the field of executive coaching. I represent this in what I call the ‘Supervision Shame Cascade’ (see Figure 1).

Many factors influence the potential for shame in coaching and supervision

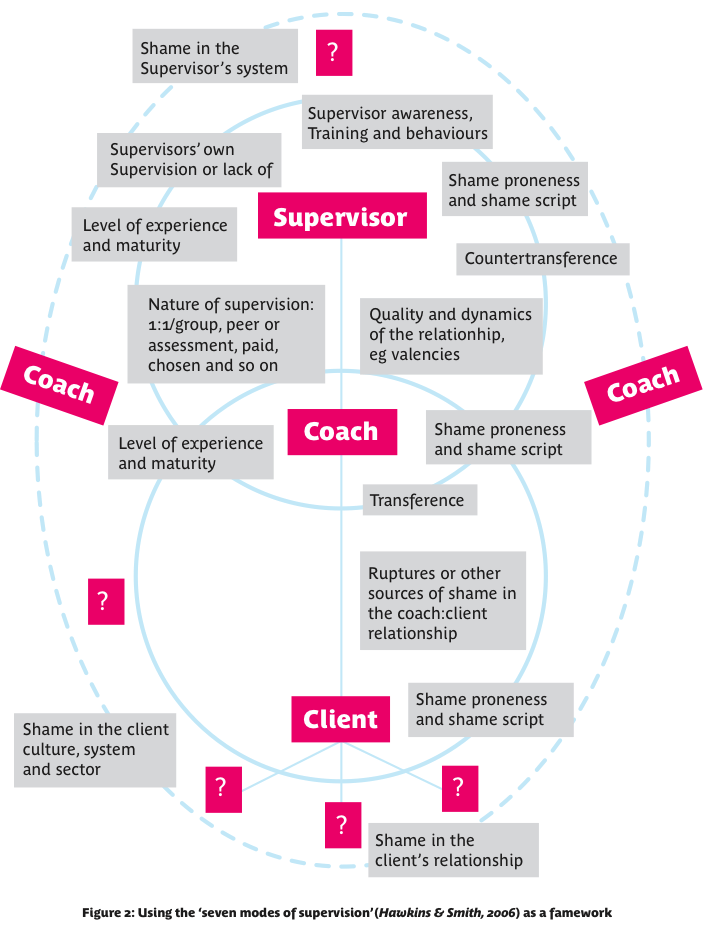

We experience shame both in relationship with others and on our own – it can be pre-existing or created in the moment. Therefore, there can be many sources of and influences on shame in coaching and coach supervision. Some of these are explored in the literature; still more are not: I summarise them here and have mapped them on to the seven-eyed model (Hawkins & Shohet, 2006; 2012) in Figure 2to use as a visual tool.

The coach Their degree of ‘shame-proneness’, perhaps relating to their own ‘shame script’; their experience; what they learnt and had modelled in their training; whether they are in training or not; how much they have explored the shame in their own lives.

The supervisorParallel factors similar to the coach listed above. As individual coaches and/or supervisors we have our own propensity to be alert to shame in a coaching or supervisory conversation, probably influenced by our unique shame script and our subsequent learning.

In turn, this will influence the way we provoke, surface or work with shame. Thirteen out of 15 respondents in my research, when answering as supervisors, said they were aware of moments when their own shame or embarrassment got in the way of their supervision practice with a supervisee.

Where I have felt inadequate or ‘wrong’ and have let that interfere and silence me

Where I have felt the supervisee’s discomfort too much and been inhibited by it

The supervisory relationship Including the degree of safety and trust, the power dynamic and mismatches in vulnerability.

The supervision setting and characteristics Independence of supervisor, choice of supervisor and payment for supervision.

My research found that all supervision settings can be shame-prone, although there was a sense that group settings are riskier and either people are less likely to disclose, or shame-related issues are less likely to be effectively explored in these settings.

The client/client relationshipCountertransference is a ready source of shame in supervision, which may manifest as parallel process. For example, Talbot (1995) describes “the therapist who feels degraded and dismissed by a patient may, by his behaviour in supervision, engender similar feelings in the supervisor”.

The wider systemThe wider organisation and/or system readily provides sources of

shame. Strikingly, 14 out of 15 respondents were aware of shame being in the organisational field when working with supervisees.

Very strong. I work in the NHS and it is a very real concept to deal with

It comes up quite a bit as the environment is pressurising people to be at their best and there are high expectations of the coach too

I’m aware of shame in the organisational field in: not being competent, making mistakes, not handling clients well, not speaking up about issues of integrity, not being able to help clients, not being able to work well together

What are the opportunities?

In my own inquiry and learning I have shifted from a sense of shame in supervision being a ‘bad’ thing, with an almost inevitable negative impact on learning, to thinking that if we take a lighter, more normalised approach (shame is universal after all), it opens up the potential for a different conversation.

Seeing shame as useful data and through a relational systemic perspective, helps transform it from a blocker to learning to a rich reservoir of insight and exploration.

Whether you are a coach, a supervisor or both, you have the opportunity to increase your awareness of shame and move towards an active sensitivity and sense of opportunity to bring things out of the shadows for mutual and system benefit.

Working with shame

Raise your awareness of shame in your practice, its potential sources and its transformative opportunities

Contract for working with shame – whether you’re a supervisor or supervisee, it’s where the richest work is to

be done

Be brave enough to name it in supervision and explicitly inquire about it to keep it front of mind, and out in the open

Explore the sources of shame in your own life and how you judge yourself: write your own shame script

Take more risks with what you take to your own supervision and co-inquire into the experience

Ensure work on shame is actively incorporated into all coach and supervision training programmes you’re involved in

Share specific approaches or tools you’ve found helpful, eg, using metaphor, normalising, self-disclosure.

In myself and I believe in all of us in the profession, this journey requires continuing and growing reflection, awareness and courage.

Don’t turn away

Keep your gaze on the bandaged place

That’s where the light enters you.

– Rumi (13th century poet)

References

B Anderson-Nathe, ‘My stomach fell through the floor: The moment of not-knowing what to do’, In: Child & Youth Services, 30(1-2), pp1-9, 2008

B Brown, Daring Greatly: How the Courage to be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent and Lead, Penguin, London, 2012

L Cozolino, The Social Neuroscience of Education: Optimizing Attachment and Learning in the Classroom, Norton, New York, pp99-109, 2013

William K Hahn, ‘The role of shame in negative therapeutic reactions’, In: Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 41(1), Spring, 2004, pp3-12

William K Hahn, ‘The experience of shame in psychotherapy supervision’, In: Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(3), Fall, 2001, pp272-282 Publisher: Division of Psychotherapy (29), American Psychological Association

P Hawkins & R Shohet, Supervision in the Helping Professions. McGraw-Hill Education (UK), 2012

N K Ladany and L R Kulp, ‘Therapist shame: Implications for therapy and supervision’, In: Shame in the Therapy Hour. R L Dearing and J P Tangney (Eds), Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association, pp307-322, 2011

L H Shelton, Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 62(8-A), Feb, 2002, pp2,683

C Soanes & A Stevenson (Eds) Concise Oxford English Dictionary, 11th edn, revised. Oxford University Press, 2008

N L Talbot, ‘Unearthing shame in the supervisory experience’, In: American Journal of Psychotherapy, 49,(3), Summer 1995, pp338-349,

A Webb, ‘What makes it difficult for the supervisee to speak?’ In: B Lawton and C Feltham (Eds), Taking Supervision Forward: Enquiries and Trends in Counselling and Psychotherapy, Sage, London, 2000