Tatiana Bachkirova, professor of coaching psychology and director of the International Centre for Coaching and Mentoring Studies at Oxford Brookes University, discusses her research on self-deception in coaches

I have been fascinated with the phenomenon of self-deception for a long time since noticing that I am quite capable of deceiving myself. It is also impossible to imagine that self-deception would not influence, at least in some way, the coaching process.

Observant coaches may notice our clients sometimes deceive themselves, for example, about their status and prospects in the organisation, not noticing ‘the bad news’ to stay in the comfort zone. Coaches are aware that clients “filter information for personal reasons” – one of the ways to describe self-deception (Fingarette, 2000).

However, coaches themselves are not immune to self-deception. They may see patterns in clients’ stories that ‘confirm’ their preferred interventions; overstep the boundaries of coaching when clients wish to work on issues more appropriate for therapy; push the client too much for their own reasons; ignore ethical dilemmas or collude with powerful clients. In this article I share some results of research I have conducted to investigate self-deception in coaches (Bachkirova, 2015).

Although it might sound like a masochistic exercise, the intention of the project was quite pragmatic: if we as coaches become more aware of our own self-deception, we are in a much better position to see more in our work of enhancing self-awareness of our clients.

The first problem with this research was to acknowledge that even defining self-deception is difficult. There are quite distinct theoretical positions on self-deception, which lead to very different views on how self-deception is recognised and can be influenced (Bachkirova, 2016a).

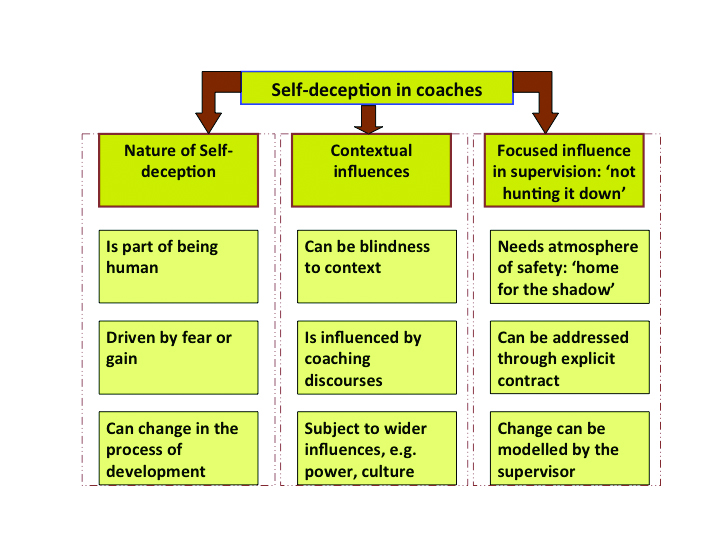

The second problem was to identify those who would be comfortable to talk about working with self-deception in themselves and others. Luckily, six experienced supervisors agreed to participate and create with me through a unique research methodology a concept or model of self-deception in coaches. The concept was changing from one interview to another until the final model was assembled (Figure 1).

The results of the study show three groups of themes: about the nature of self-deception; about influence on self-deception by the context of our work and how self-deception can be influenced in supervision.

I am going to give a brief account of one theme from each group with a ‘takeaway’ message.

The nature of self-deception

First, we have to accept that self-deception is not unusual. Those who think they are above self-deception are those most likely to suffer from it. For coaches who wish to deceive themselves less, one of the most important things is to understand how self-deception comes about in the first place.

The problem starts from a blessing: we can pay attention to specific things. If we wish to focus on something in particular from the overall field the rest of the available information becomes a background we do not register.

This selectivity helps us avoid being overloaded with irrelevant information. Self-deception is just an extended ability for selectivity when we have a reason not to notice something (Fingarette, 2000). The reason often involves self-interest: to protect us from unwanted information or to gain extra benefits (Von Hippel & Trivers, 2011).

Here is an example of self-deception recognised with hindsight by a research participant (Bachkirova, 2015). The reason for this coach not to notice the value conflict was protecting his image of a professional:

“…the client’s value base was well outside of what I do, but hell, I’m a professional, I should be able to do that, to maintain the distance etc. … What the effect of it was that actually the client was led to believe that the coach shared their views, because there was never any challenge of those views, because the coach was so busy protecting this notion that ‘I can work with it, it’s OK’.”

Therefore, one way to minimise self-deception is examining our self: what would we wish to achieve or to protect almost by any cost?

Self-deception is aggravated by contextual factors

Everything and everyone around us influences our personal self-deception. Even the fact of being a coach may add to overestimating your ability and impact because clients are often appreciative. Some features of coaching culture, for example, those that place emphasis on Positive Psychology, can add to overinflating the view that everything is possible, but that being realistic is negative or boring.

Organisational culture can contribute to a tendency for coaches to follow short-term, formulaic expectations. Coaches accept that ‘playing the game’ of setting goals in a way some organisations expect is part of being professional, but sometimes we start believing in this game and such formulaic coaching becomes a reality.

If we wish to minimise our self-deception tendency, we need to examine what values and expectations of our professional culture we adapt without questioning. These might be forming the filters in our perception that become self-deception.

What can we do about self-deception in supervision?

Supervision seems to be the most suitable place to have a conversation about self-deception in coaches. If it is part of the contract, our potential blind spots and ‘tricks of perception’ could become a great topic, being incredibly developmental for the coach and potentially adding value for our clients.

What seems clear is that for this topic to be discussed, the coach should feel secure from the judgments often associated with self-deception. The task of the supervisor becomes to create a ‘home for the shadow’ – an atmosphere in which the coach has permission to be imperfect and feel free to explore their self-deception.

If we wish to create an opportunity to explore our self-deceptions in the context of coaching we could choose to be pro-active and include such discussions in our supervision arrangement (Bachkirova, 2016b).

Although we should not expect miracles, given self-deception is part of being human, some cautious optimists would say the nature of self-deception changes when we pay attention to it.

If we are developing, we can catch our self-deceptions a little quicker than we used to.

- Tatiana Bachkirova is professor of coaching psychology and director of the International Centre for Coaching and Mentoring Studies at Oxford Brookes University

References

- T Bachkirova, ‘Self-deception in coaches: an issue in principle and a challenge for supervision’, in Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 8(1), pp4-19, 2015

- T Bachkirova, ‘A new perspective on self-deception for applied purposes’, in New Ideas in Psychology, 43, pp1-9, 2016a

- T Bachkirova, ‘The self of the coach: Conceptualization, issues, and opportunities for practitioner development’, in Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 68(2), pp143-156, 2016b

- H Fingarette, Self-Deception. London: University of California Press, 2000

- W Von Hippel and R Trivers, ‘The evolution and psychology of self-deception’, in Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 34, pp1-56, 2011

Figure 1: A model of self-deception in coaches