In this age of high exposure, what does it mean to be authentic in a workplace context, and what then does this mean for the coaching profession? Neil Tomalin shares his research

What rules now apply to the sharing of personal information in the workplace? How should we do it and what should we say? And in a world where the disclosure of personal information is regarded increasingly as the norm, what impact is this likely to have on workplace performance, and on coaching?

These were some of the salient questions for me when I embarked on my research into authenticity last year [2017].

What drew my attention to the research theme of authenticity were two basic things.

First, more employers in both the public and private sectors had started to advertise that they wanted their employees to bring their ‘true selves to work’. And second, rather coincidentally, I was attending a number of events that placed great emphasis on employees disclosing very personal information about themselves in a public arena.

Very often the subjects of disclosure were sexuality or mental health and I wasn’t sure how I should react. I was torn between jumping out of my seat with the zeal of an evangelist shouting out my own confession or remaining rigid in my seat gripping the chair tightly in order to feel safe and secure.

History is normally considered as a subject of dates and events, but in the context of authenticity it is our emotional history that we need to reflect on, and of course this is the territory of coaching. For me, there is no better example of how this is changing than the range of topics that are now on limits for discussion between my own children and myself. The contrast between this and my own parents is palpable.

The findings

In my research I experimented with this in terms of getting employees to imagine how they might behave if their own employers introduced a ‘bring yourself to work’ day. This was an invention extending the boundaries of the now well-established ‘dress down’ Friday, which is known to be effective at enhancing feelings of authenticity.

Greater freedom of dress was included in the feedback, but it also, tellingly, included the desire to be able to ‘really tell’ work colleagues what they thought of them, as well as a wish for greater inclusivity. What one respondent said struck a chord with me. He simply wanted the opportunity to talk to the company directors about strategy, and in his imagination an employer-sponsored ‘bring yourself to work’ day would give him this freedom.

The study itself was qualitative, with participation from several employers and a wider employee base. Indepth interviews focused on exploring themes around what being genuine and authentic in the workplace meant, with particular attention paid to the impact on individual performance and the scope this offered for the redefinition of employer/employee relationships. It also asked questions about how employers could be more inclusive.

The intention of the study was not to provide a definition of what authenticity means. From a very early stage, it was apparent that this was a very personal thing. More of a feeling than any standardised form of words could capture. Inspiration for expressing this feeling came from an unexpected source. A drag queen appearing in the latest UK TV series of RuPaul’s Drag Race gave a compelling and moving snapshot of how it felt and what he had gone through to find a comfortable work environment:

“I am now a modified version of that really authentic three-year-old. Work, school, being bullied and all that. That three-year-old was fierce and fearless and just so dynamic and I lost a lot of that light going through a lot of experiences and life and I’ve had to hold tight on to that individual, who would put on momma’s bathing suit and say, ‘hey’.”

One strongly emerging theme in my research was the power of human moments. By this I mean where there is a genuine heartfelt reaction to an event – both in terms of cementing business relationships and in enabling employees to feel able to be more of their authentic self.

The best example was captured within an indepth interview where an employee explained what it felt like when coming out as LGBTQ to their boss. It was moving both in terms of how that business relationship was improved, how powerful the human response was on both sides and this reflection. If the boss (described as a typical alpha male) could allow themselves to show that level of humanity and heartfelt authenticity in how he runs the business, he could be the most effective CEO in the UK.

Human moments like this when they land properly are extremely effective, and it’s perhaps in search of these that many coaches coach. The power of human moments has not been missed by our political class – both in terms of the pathos that they try to evoke in political speeches and how they react when crisis strikes. It seems almost mandatory now that a president or prime minister flies in personally to comfort those struck by disaster.

The Grenfell Tower fire disaster, which took 71 lives in London, was a recent example where the media immediately drew comparisons between the more comforting behaviour of Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn and that of prime minister Theresa May, who was more remote, but nonetheless concentrating on a solution. It is arguable that both reacted in a genuine and authentic way.

In coaching, it can be helpful to explore this power with clients, in terms of their impact and influence among others, for example, and as ways to connect with colleagues.

It will come as little surprise that for the participating employers there was a commercial bottom line, and that if the benefits of authenticity could be well-evidenced they would be prepared to make it more of a priority.

Employers were also not particularly erudite when asked about the type of relationships that might be possible with employees in this new age of personal disclosure. Added to this, size really mattered in terms of getting to know your employees and was particularly relevant when they were asked how well they thought the board of directors should know each other.

There was also a strong sense about the type of behaviours they were trying to encourage in their employees. One notable example was of a particular employee who was being very assertive in meetings. He was crashing through normal company protocols and challenging upwards very effectively.

For him, it was proving to be a very effective means of gaining attention, but how would the organisation cope if this behaviour were widespread?

These sorts of issues can usefully be explored in coaching.

Edit mode

This observation, made early in the project, was incorporated into later interviews, specifically to probe into how authenticity might differ in a meeting, as opposed to when sending an email or speaking to a colleague face-to-face.

Again, it can be explored within coaching sessions around when to behave how. It was rare among the employee interviews to find anyone who felt they could really be themselves at work. This may have been due partly to the sample selection (most were middle managers).

The picture that emerged was of a group of workers who were in edit mode, both in the workplace and on their social media. They were constantly editing and it was in meetings that their frustrations were heightened, as well as the restraints created by management hierarchy.

What also came out strongly was that to be authentic the relationship they had with their manager was key.

Coaching can be used to explore these relationships, and potentially the energy toll it might take on clients to engage in so much editing.

Is your client a dog or an owl?

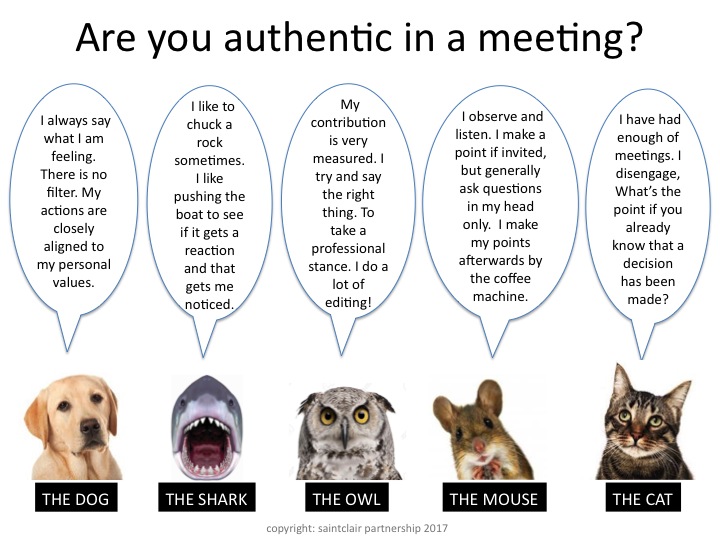

The employee research provided a fascinating insight into authenticity within meetings by identifying five typical stances. I have now adapted these to throw fresh light on what are typical behaviours, described in Figure 1 above. These can be explored with coaching clients to see which are their usual manifestations and how they might flex around different ones.

The characters can enable clients to reflect on the type of behaviour they displayed, to consider if their behaviour was consistent (as many people flit between a number of them) and the extent to which they feel they acted or act in a way that felt natural.

Having run a number of workshops since then, my interest in how we all adapt our behaviour specifically in the meeting environment has increased. It appears to be the major finding from the research that was completed.

I am left with a burning question. When I am in front of a client should I be coaching them towards their authentic and genuine self, or encouraging them to adapt their behaviour as circumstances dictate?

The answer could be: both. There are sufficient academic studies to suggest a positive link between authenticity and improved work performance, particularly among those groups who feel that they may belong to a minority group that does not have universal acceptance.

As a benchmark, coaches and clients can learn a lot by observing what goes on in meetings. This can be very effective in displaying just how inclusive a business is, a position that is normally a good indicator of how easy it is for employees to be themselves. It is also an opportunity to get noticed and gain attention depending on the tactics clients employ.

It is quite possible that I am more likely to leap to my feet the next time I attend a ‘confessional’ event, but I am hoping that the real difference comes from an analysis of my own behaviour in meetings, including in a coaching context.

It is there that I hope the real Neil Tomalin will stand up, or at least make a point with greater authenticity when sitting down!

- Neil Tomalin is managing partner and business coach at Saintclair Partnership

Trackbacks/Pingbacks