Jonathan Passmore and Eve Turner offer a practical, ethical decision-making framework, APPEAR, as a tool for use by coaches and their supervisors to help guide practitioners through ethical dilemmas in their work and to develop ethical awareness

So how much is it worth to your business to win this coaching contract with our organisation?”

This question made Jonathan Passmore sit up as he listened to a coach share their awareness that in some contexts a facilitation payment was a key stage in winning work and one that fellow coaches were willing to engage in to secure a coaching assignment.

In the UK, EU and US, such payments would be considered a bribe and unethical. In most cases these practices are expressly prohibited by professional bodies, and would lead to individuals being removed from membership and the case possibly referred to the police. A criminal conviction could then lead to a custodial sentence for both the person making the payment and others who covered up or failed to disclose the act, including supervisors.

Yet despite this illegality, and the risks involved, research suggests many coaches would not disclose such a payment if they were aware a colleague was engaging in such activities (Passmore, Brown & Csigas, 2017).

Our research with supervisors, recently published in Coaching at Work, issue 12.6, ‘The trusting kind’

(Turner & Passmore, 2017), also showed how practice related to ethical dilemmas varied between supervisors.

We made a number of recommendations related to training, the value of case studies, the role of professional bodies and the need for further research.

This experience, and other ethical dilemmas, has drawn us as coaching supervisors to consider how we can improve ethical conduct by bettering the way coaches reflect on ethical dilemmas and make more ethically informed decisions.

Building on previous work on an ethical decision-making model (Duffy & Passmore, 2010), we wanted to provide a framework that could be useful in two ways:

- For coach trainers to teach the model as a practical tool to support coaches in understanding and working with ethical codes of conduct

- For coach practitioners to move from a written professional code to a step-by-step approach that can help them when faced with the reality of a challenge or dilemma.

A six-stage model

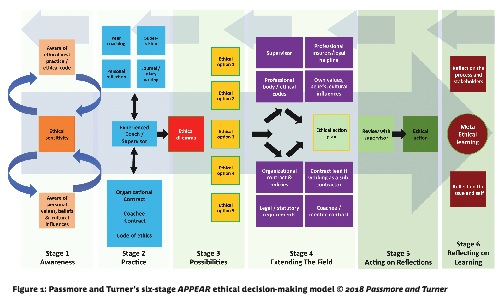

The model consists of six stages (see Figure 1). Like most frameworks we see this as non-linear and multi-iterative, with the coach and supervisor moving generally left to right, but also backwards and forwards as new data, thoughts or emotions emerge.

- Awareness

The first stage of the process is Awareness. For high-quality ethical decision-making, coaches – and their supervisors – need to be sensitive to ethical issues. This may involve an awareness of best practice, what others are doing, as well as an awareness of and understanding about the application of the relevant code from their professional body.

The second dimension is self-awareness: of our own values, beliefs and the cultural influences which affect attitudes towards what is acceptable and unacceptable conduct. These factors are sometimes embedded in law, but more often are part of national, sector, community or organisational norms.

Take the use of language. One of us has worked extensively in the oil and gas sector where the use of Anglo-Saxon language, which may be termed ‘swearing’, is common and part of daily discourse. However, in another of our clients’ offices, a Christian social action charity, such language would lead to disciplinary action or dismissal.

- Practice

The second stage is Practice. While coaches and supervisors engage in practice, ethical practice is enhanced through specific, regular actions that practitioners can take. Supervision, journalling, personal reflection and peer coaching all play a role.

The second dimension is that coaches, as part of their practice, will engage externally with clients, organisational clients, commercial coaching companies, which they may work for as associates, as well as individual clients.

As they engage in practice, entering into formal and informal contracts, verbally and in writing, they will also be aware of the codes of ethics which sit behind the contracts and support their work.

We recognise that practice can continue for weeks or months without a dilemma or ethical issue arising for the coach. It is only when such dilemmas emerge that the coach may turn to stage three of the framework, Possibilities, to help them manage the ‘red box’ of the ethical dilemma.

- Possibilities

The coach, sometimes with the help of their supervisor, or with a peer, may begin to generate alternative courses of action. We have found this may start with a dichotomy: “I can do ‘A’, or I can do ‘B’ ”, but as their reflection deepens and through conversations with others, multiple options are likely to emerge.

- Extending the field

Once generated at stage three, the coach and their supervisor are able to move to stage four: Extending the field.

In this phase, the coach aims to develop an ethical action plan by extending their thinking and considering a wider frame. This may involve a focused supervision session or advice from their indemnity insurance provider’s helpline. It may involve a detailed review of their ethical code of practice, and it will certainly involve a deep reflection on the coaches’ personal values, beliefs and assumptions about the case.

Other sources are also likely to be worthy of consultation, review and reflection in helping the coach extend their thinking. This includes a range of contracts and policies: the organisation’s, the coach’s or coaching provider’s contract with the organisation, the coach’s own contract with the coach provider if they are working as an associate, and their personal contract or agreement with their coachee. Again, these may be silent on the specifics, but together may provide an insight into the appropriate course of action.

- Acting on reflections

Our fifth stage, Acting on reflections, is about implementing the appropriate course of action. Prior to doing so, working through the action plan, steps, stages, timing and sequence can be enhanced by a discussion with a supervisor, who can both support thinking and act as devil’s advocate to help reflect on the practical aspects of our action, and prepare for the possible responses of different actors who may be affected by our actions.

- Reflecting on learning

The final stage in our six stages is for the coach to reflect on their learning. This reflection should be at two levels:

- Reflection of the process and the various stakeholders, and what they have learnt as a coach from thinking through and implementing this ethical action

- Reflection on the issue and themselves. What have they learnt about themselves in this process? How has the issue and its resolution affected them through the various stages of the process?

Such reflection, done well, can lead to new insights and a contribution to our continual developmental journey.

Conclusions

The APPEAR model does not guarantee a successful outcome in all circumstances. But using its staged approach, to encourage coaches to develop greater sensitivity and awareness in their practice, to be more mindful of ethical decision-making as an active process, considering a wide range of factors beyond simply checking professional ethical codes, we hope will help practitioners adopt a more reflective process to the resolution of ethical dilemmas.

- Jonathan Passmore is director of the Henley Centre for Coaching. He is a chartered psychologist, holds five degrees and has won several awards for his research and practice in coaching and psychology. In 2017 he was awarded the British Psychological Society’s ‘Distinguished Contribution to

Coaching’ Award - Eve Turner is a visiting fellow at the University of Southampton and an accredited master executive coach and supervisor, who was the EMCC’s Coach of the Year, 2015. She holds awards and nominations for her writing, research, coaching and supervision work. She has set up the Global Supervisors’ Network to promote development in supervision: www.eve-turner.com/global-supervisors-network/

APPEAR model

The APPEAR model offers a step-by-step process we hope will aid coaches and supervisors to be both more ethically aware and capable, enhancing their ethical decision-making in practice either individually or in partnership with their supervisor.

The model has six stages:

- Awareness

- Practice

- Possibilities

- Extending the field

- Acting on reflections

- Reflecting on learning

At any point the coach, mentor or supervisor may go back to an earlier stage.

Case study: Samira and Glen

Samira was working with several clients in a large organisation. One of her clients, let’s call her ‘Peggy’, had an undisclosed disability. Peggy confided in Samira, but insisted the organisation shouldn’t know. However, separately Samira was hearing from other clients that they were so disturbed by some of Peggy’s behaviour, directly influenced by the disability, that they planned to go to the director and ask for her to be fired.

In the case of Glen, his client, let’s say William, was claiming he was being bullied. This was having a detrimental impact on his work performance and his personal life. A further complication was that Glen was working for a third party that had won the coaching work, and the third party’s link for what was a lucrative contract was the person William claimed was bullying him.

We pick up the story at stage three (see Figure 1) with Samira and Glen. They are both experienced members of professional bodies, have regular supervision, are involved in peer work and are experienced in stakeholder contracting where the organisation is involved. They had generated a number of options.

They found stage four particularly helpful as a useful checklist around responsibilities, and included some aspects that, in the moment (stage three), had not occurred to them, such as going to their insurers or coaching body. They also both felt the key importance of contracting thoroughly and openly was underlined; they would also note any relevant organisational policies.

Samira commented that she hadn’t considered that by not disclosing to the organisation, one possible outcome could have been her being party to a case for unfair dismissal – a call to the insurers and a discussion with the helpline could have aided here.

Another element that emerged for Samira, in looking at the model, was that it supported her to be more systemic in her thinking and stay in the role of the detached, if compassionate, observer, and avoid being sucked into the world view of the client.

For Glen, the contract lead in the third party for whom he was doing the associate work was particularly supportive, and enabled a way forward that bypassed their link person in the organisation.

Samira and Glen felt that meta-learning, as in stage six, was essential. Spending the time to reflect on the different elements that have emerged, both systemically and from the process and also on learning about ourselves and our own issues, gives us a greater understanding of some of our ‘hot buttons’, or potential omissions.

References

- M Duffy and J Passmore, ‘Ethics in coaching: An ethical decision making framework for coaching psychologists’, in International Coaching Psychology Review, 5(2), pp140-151, 2010

- J Passmore, H Brown, Z Csigas and the European Coaching and Mentoring Research Consortium, The State of Play in European Coaching & Mentoring – Executive Report, Henley-on-Thames: Henley Business School and EMCC International, 2017 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.225085.26080

- E Turner and J Passmore, ‘The trusting kind’, in Coaching at Work, 12(6), pp34-39, 2017