We need to radically change our understanding of the impact of the coaching relationship and the role of the client on coaching effectiveness, says Erik de Haan. Following on from his co-authored article last issue on a randomised controlled trial (RCT) in the healthcare setting, he draws conclusions from this and another RCT, with co-author, Joanna Molyn

This article follows on from last issue’s report on the first of two recent large-scale randomised controlled trials (RCTs), an experiment at senior levels in an industrial setting.

It examines this RCT further along with another in a business school context. Each RCT demonstrated considerable and significant coaching effectiveness, pointing to aspects which make executive coaching a particularly strong intervention at senior levels. And they show that we have to radically change our understanding of the impact of the coaching relationship, in the shape of the ‘Working Alliance’, on coaching effectiveness.

Undoubtedly, executive coaching is becoming increasingly important. The factors include:

- There’s a general impression that our rapidly changing businesses demand a higher engagement from the whole person in organisations (ie, including our personal sensitivity, intuition and feelings) and as executive coaching is tailored to the specific, current goals and needs of the leader, it seems particularly well placed to address this.

- There’s a growing number of successful implementations, eg, ‘internal coaching’, ‘performance coaching’, ‘first 100-days coaching’, and ‘team coaching’.

- Effectiveness of executive coaching seems to be rather well demonstrated in recent years; moreover, research in this field confirms the high effectiveness in adjacent professions such as mentoring, counselling and psychotherapy.

The big question though, is what makes coaching so effective, ie, what are its ‘active ingredients’? If we knew more about such factors, we could adapt the training, education and selection of coaches, and model our coaching approaches, interventions and contracts around ingredients that have been demonstrated to contribute most to outcome. However, clear consensus about active ingredients has so far been elusive, and this new research seems to indicate why this may be the case.

The experiments

Our first experiment, featured in the previous issue of Coaching at Work (issue 14.6; De Haan, Bonneywell and Gammons, 2019), was the largest RCT undertaken to date in coaching. The setting was a realistic one for executive coaching: a global healthcare company, comprising approximately 100,000 employees based in more than 120 countries (De Haan, Gray and Bonneywell, 2019). We involved two consecutive groups on a leadership development programme exclusively based on coaching and designed to increase the ratio of female leaders at all leadership levels.

The two starting points of April and September provided ideal conditions for a ‘waiting list control group’ design, with 89 female leaders in the target group and 72 female leaders in the control group (the September intake), with at least 114 corresponding questionnaires from their 66 coaches and 115 from their 140 line managers.

This RCT found strong support that executive coaching was a highly effective intervention; not only in the eyes of the clients but also in the eyes of their line managers, with effect sizes d larger than 1, an indication that clients were better off than at least 85% of those in the control group.

This result confirmed meta-analysis studies such as Jones et al’s (2015). By using a randomised control group, we know the effectiveness can be attributed to the intervention itself. Moreover, thanks to measuring effectiveness through the eyes of coaches, clients and line managers we know the finding is robust against same source bias.

We also found support for factors contributing to this effectiveness, in particular client-related factors such as Resilience, Self-efficacy, Perceived Social Support and Mental Wellbeing, and also for the Working Alliance between coach and client. Although the study was undertaken in the healthcare industry, we believe these findings are globally generalisable over many industries, because clients were globally mobile, senior and general managers, not technical healthcare experts.

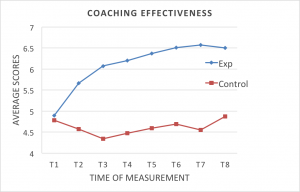

In the second RCT study led by Joanna Molyn (Molyn, De Haan, Stride and Gray, 2019), an even larger group of 105 business school students at a London university (average age 23) were coached by an equal number of qualified coaches, while another 105 students formed the control group. We collected data over eight data points for clients and coaches, enabling us to model the expected ‘dose-effect’ curve over the course of the coaching sessions (see Figure 1). In this study we established significant change on a range of parameters: coaching effectiveness, Resilience, (lower) stress and goal attainment scores. Again, we found evidence for similar factors contributing to this, namely Hope, outcome expectations, Self-efficacy, Perceived Social Support, and also for the Working Alliance between coach and client.

It was reassuring to see two RCTs studying executive and workplace coaching find the same effect sizes in very different contexts (senior manager clients vs. student clients; global business setting vs. local business-school setting; leadership development programme vs. paid subjects in student context; two different groups of qualified coaches, etc.). They both find significant results on ‘Coaching Effectiveness’, while the first study also measures the impact on Leadership Personality (according to the Hogan psychometric) and the second study measures effects on other variables such as Goal Achievement, Resilience and Mental Wellbeing improvement, as well as Stress Reduction.

However, there was also an important surprise when comparing the two studies. In the second study we could only detect significant effects of Hope, Perceived Social Support and Working Alliance ratings on the levels of effectiveness, not on the change in effectiveness during the coaching.

This means it is now harder than before to associate these variables with the change through coaching per se. We now think that this means that we will have to revise our thinking about coaching effectiveness profoundly.

Beyond correlation

The older studies on the impact of the coaching relationship, which have been summarised in a meta-analysis (Grassman et al, 2019), show consistently that Working Alliance (as measured by the Working Alliance Inventory – WAI) is linked to outcome. We have now found that, even though WAI correlates with coaching outcome throughout, ie, at different time points, WAI does not correlate with any increase in coaching outcome from the second session onwards.

This can only be explained as WAI being important in terms of a general readiness for coaching, ie, for initial or average values of outcome, but not for the impact, the effectiveness of the coaching intervention itself.

Until this study there has only been correlational research into the impact of the alliance, involving a single measurement of WAI, and therefore causality has been beyond the reach of other studies (Grassman et al, 2019).

Findings

I believe that WAI has perhaps been misconstrued and misnamed as a relational variable, one that might tell us about the strength of the relationship in the coaching room. Instead, it is perhaps more justified to see it as a measure of a client propensity to relate, ie, not a relational variable but a client-related variable. The Working Alliance ratings by a client may tell us mostly about the client, about how disposed the client is, generally, towards a good working relationship, and how easily the client thinks s/he engages in a relationship that s/he rates positively (eg, from the Agreement on Task, Agreement on Goal, and Bond perspectives).

This picture is confirmed by the fact that client and coach scores of the Working Alliance only show a very limited correlation (De Haan et al, 2016), and are both barely related to observer scores of the same relationship (Gessnitzer & Kauffeld, 2015).

All earlier findings (Grassman et al, 2019) can now be understood to show that clients who say they ‘relate’ better, also achieve better results in coaching, at least according to their own estimates, to an extent confirmed by their coaches and line managers. We think WAI measures a relatively stable client personality ‘trait’, as also in this study; however, some of WAI may also be measuring a more changing aspect of personality – a ‘state’. The fact that WAI levels did increase on average during the coaching journey confirms that there are ‘state’-like aspects present as well in the WAI scores.

However, what is important for coaching outcome research, is that the client’s relationship scores do not seem to drive outcomes: the sense of relating well with your coach gives clients a higher outcome overall but is hardly influenced by the sessions themselves. In fact, in the second study we found the client’s Resilience scores to be a much better predictor of outcome, to such an extent that most of the predictive power of other client variables were picked up and carried by Resilience alone.

This helps explain why so little evidence has been found for additional effectiveness to be had from particular ‘matching’ between client and coach (Page and De Haan, 2014): there are certain traits that give clients an overall increase in effectiveness (such as WAI, Hope, Self-efficacy) but they are hardly further improved by the sessions themselves or the coach match.

It appears that clients rate their experience in coaching with a ‘halo effect’. The client will rate all aspects of the experience as better or worse, in accordance with how useful the general experience was for them and with their own optimism about helping relationships (significantly influenced by client-based factors such as Hope, Expectancy, Self-efficacy, Resilience, Mental Wellbeing, and even, now, Working Alliance) and will then score all outcome aspects accordingly.

It’s worth reporting that each of the studies has also demonstrated a particular reason why coaching is so very helpful for senior leaders:

- The second study shows Resilience is an important driver of outcome, while we know that today mental toughness and resilience are pervasive qualities of our executive coaching clients. So, statistically, tough top leaders are expected to do well in coaching.

- The first study, though, showed coaching has a significant beneficial effect on ‘personality derailers’ in leadership, the kind of personality overdrives that get leaders in trouble with their staff and their mission. Specifically, coaching seems to have a small but significant calming, balancing and responsibility-enhancing effect on personality (De Haan et al, 2019). So again, executive coaching seems highly relevant at top levels of organisational leadership (De Haan and Kasozi, 2013).

In my opinion there’s still a lot more work to do to discover what makes coaching effective. Most of the active ingredients to date are related to clients, not to anything in the sessions. We believe it’s important to start thinking differently in terms of outcomes. It seems potential active ingredients are more general than we have suggested so far: something to do with optimism and stamina on the client’s side, including positive feelings about techniques and the relationship. We will have to look at more objective outcome measures, more longitudinal trials, and at ‘holistic’ variables that can capture the whole experience in an integrated way, such as around technique and behaviour, personality of client and coach, and the in-between or coaching relationship. The latter should perhaps focus more on the atmosphere in the room and the critical aspects of sessions.

- Erik de Haan is director of Ashridge Centre for Coaching at Hult International Business School

erik.dehaan@ashridge.org.uk -

Dr Joanna Molyn is senior lecturer, business faculty, University of Greenwich

References

- E de Haan, A Grant, Y Burger and P-O Eriksson, ‘A large-scale study of executive coaching outcome: The relative contributions of working relationship, personality match, and Self-efficacy,’ in Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 68 (3), 189-207, 2016

- E de Haan, S Bonneywell and S Gammons, ‘Trial effects,’ in Coaching at Work, 14(6), 32-36, 2019

- E de Haan, D E Gray and S Bonneywell, ‘Executive coaching outcome research in a field setting: A near-randomized controlled trial study in a global healthcare corporation,’ in Academy of Management Learning and Education, 2019

- E de Haan and A Kasozi, The Leadership Shadow: How to recognise and avoid derailment, hubris and overdrive, London: Kogan Page, 2014

- S Gessnitzer and S Kauffeld, ‘The Working Alliance in coaching: Why behavior is the key to success,’ in Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 51(2), 177–197, 2015

- C Grassman, F Scholmerich and C C Schermuly, ‘The relationship between Working Alliance and client outcomes in coaching: A meta-analysis’ in Human Relations, 1-24, 2019

- R J Jones, S A Woods and Y Guillaume, ‘A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of executive coaching at improving work-based performance and moderators of coaching effectiveness’, British Psychological Society Annual Division of Occupational Psychology Conference, 06/01–08/01/14, Brighton, 2014

- J Molyn, E de Haan, C Stride and D E Gray, ‘The contribution of common factors to coaching effectiveness: Lessons from psychotherapy outcome research,’ in Quantitative Psychology, to be submitted in 2020

- N Page and E de Haan,‘Does coaching work? …and if so, how?’ in The Psychologist, 27(8), 582-586, 2014

Figure 1: The first dose-effect curve in executive coaching, confirming clear benefits throughout the six coaching sessions and a diminishing return per session. Time T1 is before the first session, time T7 is shortly after the sixth session, and time T8 is a three-month follow up, which explains why the curve bends back