Generalising and coaching in terms of generations is nonsensical and discriminatory. Better to be informed by lifespan development research, and treat each client as an individual, argues Bob Garvey

It seems that a lot of attention is being given to the millennial category of generations (see Coaching at Work Vol 14, Issues 1, 2 & 3).

This article explores some of the discourses and recent research on the topic, and considers the implications for the coaching world.

Popular discourse

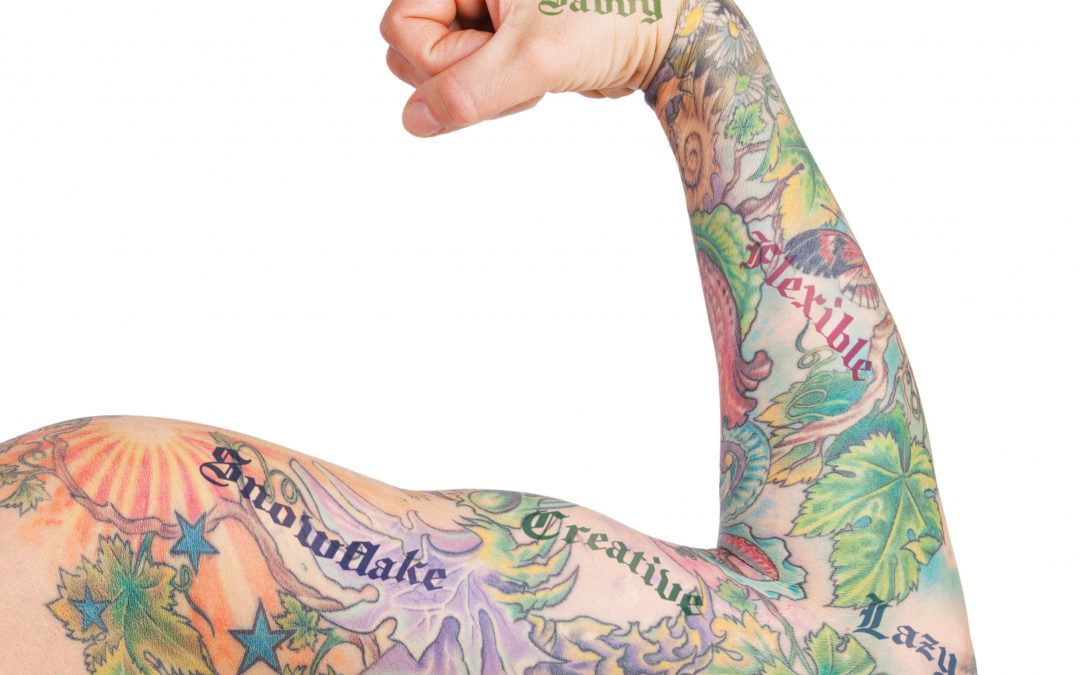

There is a mass of material on generational difference. A recent search using the term ‘millennial UK’ got 19.6 million hits. Generally, this material states that millennials have the following characteristics:

- Different work ethic

- Lazy

- Self-involved

- Politically apathetic narcissists

- Can’t function without a smartphone

- Live in perpetual adolescence

- Not committed

Is this a case of one generation complaining about another in the style of Bob Dylan’s song, The Times They are a-Changin’? On the plus side, millennials are also described as:

- Creative

- Flexible

- Open-minded

- A sense of social responsibility

- Concerned for the environment

- Tech savvy

Business discourse

The business press has similar themes but they add that millennials are:

- More confident

- Teachable

- More pampered

- Risk-averse

- In need of constant feedback and praise

- Dress badly

- Can’t keep to time

- Need clear goals and instructions

Other business discourses suggest that millennials:

- Have outlandish expectations

- Feel entitled and superior

- Hate long hours

- Expect flexible work routines

- Are disloyal

- Expect immediate access to the senior people

- Are tech savvy

They are known as the ‘me, me’ generation.

Baby Boomers (the previous generation) are blamed for this in the business press because they lavished unwarranted praise on their children and built their offspring’s egos beyond realistic expectations.

The business discourse is that millennials are hard to manage and in terms of coaching, they need special treatment.

The HR discourse

HR’s advice on managing these ‘difficult people’ is to accommodate them by investing in training, development and career growth activity. They suggest that millennials need help to understand how they contribute to the company’s mission and make their work ‘meaningful’. Also, organisations should provide millennials with more paid leave and create flexible working arrangements.

It strikes me that these ‘changes’ are just good management practice and not something unique to any particular group.

Coaching discourses

Here, coaching draws on similar discourses about millennials as outlined above. The ‘problem’ of millennials is on the conference agenda, on the pages of Coaching at Work and in other media. There are coaches promoting this concept of difference.

Is this generation a ‘problem’ or is it the case that different generations have always complained about each other and now with fast communication and social media, it is easy to spread the problem for commercial gain?

The research

There are problems associated with the idea of categorisation by generation. Neither sociology nor psychology can agree a definition of generational difference.

There is no agreed time frame for the category of millennials. Strauss and Howe (1991) offer the widest age range – an individual born between 1982 and 2004. This seems huge. In the US in 2016, this category accounted for 71 million people.

Is it possible that such a huge number of people really share the same traits? It could be analogous with stating that all people from, say, Liverpool or certain ethnic or religious groups are the same.

Historically, research on generational difference has two main perspectives: social forces and cohort. Let’s look at these in turn.

Social forces

Mannheim (1952) argues that a generation is a social group defined by birth dates, whose members share events and experiences that influence their life and behaviour. He suggests that attitudes are shaped within generations and that generational difference is a force for social change.

Joshi et al (2011) state that each generation, when faced with the norms of ‘acceptable behaviour’ imposed by previous generations, must either choose to accept or defy these norms. Young people, Mannheim claims, are more willing to accept ‘new’ ideas and are able to use their ‘new’ perspectives as a force for social change – the argument of singer and poet Bob Dylan.

Cohort

Ryder (1965, p.845) defines a cohort as a group of individuals “who experience the same event within the same time interval”. His research offers an alternative to the social force argument. He agrees that there are boundaries between generations, drawn according to birth years, and that birth cohorts may share similar experiences and events in their lives through time. However, Ryder (1965) states that the concept of ‘generation’ is a theoretical, convenience category based on generalised assumptions and there’s no evidence that an event shared within a generation leads to certain attitudes or behaviours.

Current research

Campbell et al (2017) looked at values and attitudes over time in work and found some differences between generations but also found evidence that generational boundaries are “fuzzy” social constructs. They concluded that a cohort view of generational difference is an unsophisticated indicator.

Ryder’s (1965) criticisms are also reflected in current research. With data drawn mainly from surveys, which are essentially ‘broad stroke’ research instruments – easy to do with little in-depth analysis, it’s inevitable that we end up with generalised categories that say little about specifics and contexts.

A recent PhD study (Crabbe, 2018, p.27) cites 11 pieces of research that state that age is not a factor in technology anxiety. She found that 25% of first year business students suffered from technology anxiety – so much for the tech savvy of millennials argument.

Lifespan – the holistic way forward?

These obvious problems within generational research have led researchers to a more subtle approach.

Baltes (1987) offered the idea of a lifespan developmental perspective. He suggested that human ageing is best understood as a complex process that takes into account the influences of biology and sociocultural factors across time. Lifespan researchers look for linkages across disciplines and understand development across multiple levels. It takes into account the variability of human experience and the variations of interpretation of those experiences. It considers the universal potential for human growth and development – whatever the age of the individual. Lifespan research seeks to understand developmental influences that may affect an individual’s motives, values, and attitudes at work. Learning is not a function of age!

Rudolph and Zacher (2017) suggest lifespan research needs to be focused on the individual and not treated as shared phenomena that everyone ‘catches’ off each other. They recommend practitioners recognise ageing as an ongoing developmental process – people’s lives are dynamic and all people learn. Practitioners therefore need to be cautious about creating policies and practices to put people in generational boxes. Enter coaching.

Coaching across generations (Garvey, 2013)

The search term ‘coaching millennials’ gets 5.8 million hits. This high number suggests that people in the coaching world think it is a ‘thing’. To offer some insight into this phenomenon, one hit offered the following advice to coaches:

- Provide structure and sharpen their focus.

- Create opportunities for growth. Most millennials I’ve encountered are very self-confident.

- Encourage ‘quick wins’. Every new assignment can be exciting at the beginning.

- Foster an environment for learning. Millennials love flat hierarchies.

I wonder what is unique about this offering? What assumptions do these make about coaching? Surely, these are the kinds of thing a coach would do with anyone?

We know as coaches that not every individual we coach understands or relates to similar events in the same way. Yet, I’m aware that there are coaches creating ‘models’ of coaching to take into account ‘broad stroke’ categories of people. The risk of this is that we ‘other’ people by saying ‘this group needs this and that group needs the other’. That is surely against an overarching coaching philosophy?

Coaching is for the individual, personal hopes and fears, wants and needs irrespective of the client’s birthdate, religion, country of origin or sexual orientation. This is a diversity issue and if we as coaches believe in diversity, we need to grasp the challenge and accept that we cannot be lumped together in boxes for the convenience of a coaching model. That road leads to discrimination.

With thanks to Lianne Parker-Lyn for inspiring my thinking

References

- P B Baltes, ‘Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline’, in Developmental Psychology, 23, 611–626, 1987

- S Campbell, J Twenge and WK Campbell, ‘Fuzzy but useful constructs: Making sense of the differences between generations’ in Work, Aging and Retirement, 3, 130-139, 2017

- S J Crabbe, Computer anxiety: The development of tools to measure severity and type, and offer appropriate mitigation strategies, Unpublished PhD research, University of Newcastle, https://theses.ncl.ac.uk/jspui/bitstream/10443/4382/1/Crabbe%20S%202018.pdf (accessed 16/08/19), 2018

- B Garvey, ‘Coaching people through life transitions’, In Diversity in Coaching, Ed. Jonathan Passmore, Kogan Page, 2013

- A Joshi, J C Dencker and G Frantz, ‘Generations in organizations’, in Research in Organizational Behavior, 31, 177-205, 2011

- K Mannheim, ‘The problem of generations’, in Kecskemeti, P (ed), Karl Mannheim Essays, Routledge, 1952

- C W Rudolph and H Zacher, ‘Considering generations from a lifespan developmental perspective’, in Work, Aging and Retirement, 3, 113–129, 2017

- N B Ryder, ‘The cohort in the study of social change’, in American Sociological Review, 30, 843-861, 1965

- W Strauss and N Howe, Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069, Harper Perennial, 1991