Jeremy Gomm and Jan Allon-Smith share The Coaching House, a framework they’ve developed to illuminate the many potential roles of coaches and clients

Coaches can support clients’ personal and professional development and wellbeing in many ways. Our Coaching House framework, which we introduce here, helps shine the spotlight on the different potential roles we can play as coaches, so we can choose which is most appropriate and useful to our clients at any time, and recognise which we and/or our clients may be avoiding.

Coaching may draw the coach into a range of roles including: co-creative idea generator, challenger of values and beliefs, mindful and caring ally or a supportive analyst. These roles tend to be thrust upon us by clients’ expectations and needs. Although we may want to resist some – trusted adviser, wise counsel, a shoulder to cry on, perhaps – with experience, we can flex our ability to operate in these various roles as we develop in our understanding and practice as coaches.

Although some topics are raised frequently, no two coaching conversations are the same and while we might use frameworks such as GROW (Whitmore, 1992) or OSKAR (McKergow and Jackson, 2000) to shape the conversation and help us recognise the ‘what’ of coaching conversations, they don’t really address the ‘how’. How do we see our role/s in each conversation or intervention? How many roles do we have? How do we know which to adopt and when? How do we envisage or describe our responses to the client?

Hewson and Carroll (2016) use the image of a ‘supervision house’ in which different rooms represent different aspects of supervision. Their model illustrates the nature of the various conversations in the ‘house’, exploring the roles of the supervisor and of the coach. It offers clarity about what’s happening for both parties in the supervision space and why sometimes our conversations may falter.

This prompted the idea of a similar framework for coaching to illustrate the different conversations and roles coaches occupy and to enable the coach to move from role to role, or room to room, with confidence and purpose. It also offers a vocabulary to describe and explore coaching practice in personal review and supervision.

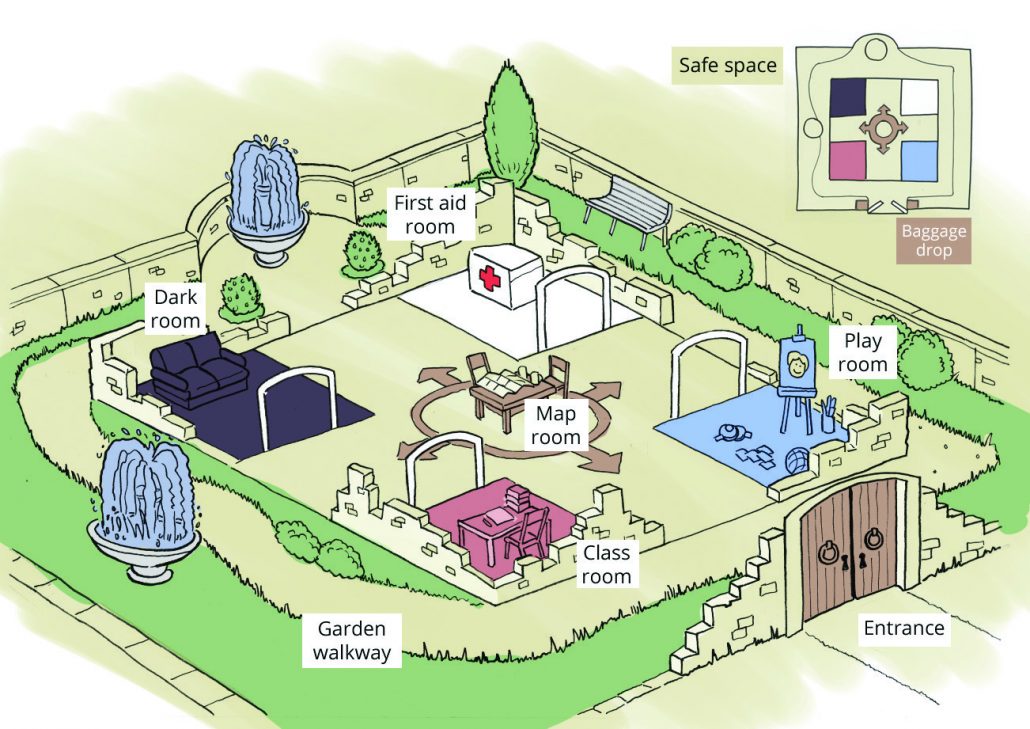

As we considered the rooms we might find in a ‘Coaching House’, we imagined a physical environment to clarify and enrich the metaphor. Apart from entering and leaving it at the same point, coach and client are free to move together about the rooms in the workspace (not a home) as they wish to be most productive. As you explore it, please consider how your own Coaching House might differ from ours, choosing descriptors and alterations that suit your own thinking. Bear in mind this is a metaphor to aid reflection and learning, not to channel or proscribe activity.

Designed to enable ease of movement from one area to another, our Coaching House comprises a protected, open space within a walled garden. The illustration (above), by John Cooper, indicates a cut-out section of the walls around each room showing that the spaces are partly enclosed but have easy access to each other. The roof is missing so the spaces are visible.

In our experience, most of our coaching takes place in the central space, focused primarily on the client’s territory, and in the garden, primarily focused on the client’s wellbeing. There are four other spaces with specific purposes.

We summarise the focus of each space and the role of the coach in it. We also identify the role of the client, if this space is to serve them well (they will probably be unaware of this). However, recognising the space the client is occupying will help clarify the role the coach needs to adopt. For the conversation to be at its best, coach and client need to be in the same room.

First and foremost in the coaching relationship is the creation of a safe space within which the coaching conversation can take place. In our metaphorical Coaching House, the safe space is everything inside the outer garden wall. In reality, coaching conversations occur in physical spaces, sometimes unprotected by real walls. Increasingly, coaching conversations are in virtual spaces, with two separate physical spaces, at either end of the link. These spaces are safe only if both parties are satisfied that they are.

Coach and client share responsibility for the care of the safe space, hence the Coaching House gateway requires two keys, both needed to open the gate. If either feels the space is unsafe, the gate can’t be opened and the coaching cannot take place or risks being ineffective.

There are two Baggage drop spaces at the entrance (behind the wall in our illustration) where coach and client can leave things on the way in and pick them up again on the way out. For the coach, these might be things on your mind that aren’t relevant to this conversation or might distract you; for the client, some of these things may later be shared, informing the coaching conversation, as the client becomes more self-aware and more trusting of the coaching relationship.

Garden Walkway:

Reflective space

Focus: the client’s wellbeing – providing time to think, wonder, celebrate and enjoy, relax, let go and to restore

Coach’s role: reflective observer, supportively challenging

Client’s role: relaxed reflection, open to celebration and to wonder, welcome peace

This is the first space the coach and client occupy when they meet. It’s a relaxing environment where they become comfortable with one another before choosing a room to move into for the next part of the conversation.

Here the coach focuses on the client’s safety and wellbeing: helping them to relax, embrace the here and now, enjoy pleasing memories and wonder about opportunities. As reflective observer, the coach listens without judgement, shares with empathy and supportively challenges.

This space is accessible from every other space. It’s restorative and relaxing, promotes reflection and is a place where it’s safe to ‘not know’. The Garden Walkway is always the starting and finishing point but the duration and frequency of time spent here depends on how the conversation develops. Our experience is that much of most coaching conversations takes place here.

Map Room:

Active space

Focus: the client’s territory – exploration of the here and now, setting goals, solving problems, planning and reviewing progress; contracting and re-contracting

Coach’s role: mindful ally and guide

Client’s role: reporting, goal setting, action planning

The Map Room is where the client’s territory is revealed and developed, another large, accessible space because much of a coaching conversation will take place here too.

It is here we gain an understanding of the client’s landscape, exploring questions such as what their interest is, how they reached this point, where they’re going, and where they want to be. To do this we must be excellent listeners, prepared to challenge and prompt to generate enlightenment for ourselves and our clients about the extent and shape of the territory, and to help the client to find ways forward, perhaps setting goals and navigating obstacles.

Ahead of all this is the creation and acceptance of a contract, practical and psychological, of how coach and client will work together, what the boundaries are and the expectations we have of each other. Some of this may be fixed in advance of coach and client getting together, or at a ‘chemistry’ session, or may be addressed at the start of the first coaching appointment. Affirming and modifying the contract will be part of the Map Room conversation.

Play Room:

Creative space

Focus: ideas and inspiration – stimulating new ideas, thinking and perspectives; finding innovative solutions to intractable problems; revealing hidden ambitions and fresh inspiration

Coach’s role: to provoke and delight in the client’s ideas

Client’s role: open-minded explorer of ideas and possibilities, wakeful dreamer

There are times when exploring the territory in the Map Room unveils feelings or thoughts that need a more expansive space. This is the blue-sky blank-page room, where anything and everything can be rethought, and something new invented.

The client may want to explore ideas and possibilities with no goal in mind. Or perhaps take an innovative approach to solving a problem. Coaching support may stimulate new thinking and perspectives or help clients to reveal hidden ambitions and aspirations, recognise the drivers – values and assumptions – that lie behind them, building on what works and encouraging new possibilities.

Dark Room:

Space for reflective exploration, self-insight and self-acceptance

Focus: discomforting thoughts and feelings undermining self-esteem, sowing the seeds of self-doubt and fracturing self-confidence

Coach’s role: gently challenging, delicately examining damaging thoughts and feelings; being aware of boundaries

Client’s role: willing to confide, deeply reflective

This is a special place in which any negatives in the client’s mind can be gently coaxed, and reframed, into clearer and hopefully more positive pictures.

Sometimes clients need space to address uncomfortable feelings, failures or blockages; a belief or assumption obstructing new thinking, undermining self-belief or confidence or preventing a behavioural shift. The coach’s empathetic listening and intuition are important here as is gentle, thoughtful challenge to uncover hidden layers, conscious of their own boundaries as the client engages in deep reflection.

Class Room:

Space for a little tuition

Focus: sharing knowledge and experience to restore self-learning and self-development

Coach’s role: tutor/mentor, offerings and illustrations to reconnect the client with the process of self-development

Client’s role: learner

Coaches believe our clients have the answers to their own questions, the resources to achieve their ambitions, and that our job is to help them recognise, accept and work with the inner knowledge and expertise that surfaces during coaching. But if clients are stuck, they may need external stimulus to access this inner knowledge. So we might offer some illustrations, examples, stories from our own experiences or work with other clients.

The coach may have knowledge the client needs – to lead, manage, or achieve what they want – and offers wise questions to the client. A client lacking knowledge or experience or who has run out of ideas or energy will find relief and will value the guidance or direction offered in the Class Room.

First Aid Room:

Space for urgent repairs and comfort

Focus: alarming, unethical or illegal behaviour, sadness or despair that needs to be aired, the coaching relationship

Coach’s role: nurse, comforter, mindful colleague, co-collaborator

Client’s role: patient, colleague, co-collaborator

In this room the coach offers whatever’s required to address issues in need of urgent repair. It might be the relationship between the coach and the client, an alarming, unethical or illegal behaviour that the client is displaying or dealing with, or an outburst of emotion, of sadness or despair.

The coach can address such issues in different ways using familiar coaching tools, holding the space while emotion is expressed and processed, combining the equivalent of a comforting cloak with a glass of water to clear the client’s head and refresh their thinking. It’s here the coach as mindful friend is tested to the full.

In practice

Each encounter and outcome from these various spaces contributes to an understanding of the client’s territory.

Progressing through a series of coaching conversations from contracting to conclusion, the coach will recognise and facilitate the flow between these roles, and the client trusts us to know which role is appropriate at each stage. The coach may be explicit about the role being taken, depending on circumstances.

The direction of the conversation, the rooms visited, is generally led by the client – creating their own learning space, wandering from room to room (unaware of the coach’s framework or metaphorical house unless it’s been shared.).

Recognising that it’s best for coach and client to be in the same room helps us consider which role the client is adopting at any point and which role this requires of us. We can ask ourselves questions such as:

- Where is the client at this point?

- What are the client’s needs which require me to respond?

- How do I respond at this phase of the conversation?

- Which intervention(s) meet/s this need?

Let’s explore an example of using the Coaching House framework to work with a client dealing with conflict. Consider a conflict-related issue that frequently arises in coaching. Perhaps conflict between the client and a manager, between other colleagues, affecting the client’s wellbeing, or conflict of values between client and organisation. Where might the coaching conversation start?

If the client is distressed, it might start in the First Aid Room, until the client is ready to move on; perhaps to the Garden Walkway, to metaphorically breathe fresh air; or to the Map Room to consider actions or maybe into the Play Room to rethink the situation.

If the problem is entirely new to the client, who is unsure how to approach it, time in the Map Room delineating the issues and then in the Class Room may offer a way forward.

If the conflict is challenging the client’s values or beliefs and undermining self-worth or self-confidence, they may need some time in the Dark Room.

The Garden Walkway will probably figure at some point in all of these conversations, to attend to the client’s wellbeing, providing time to re-group.

The conversation may move between rooms without us noticing it. The client may be in the middle of goal-setting in the Map Room and suddenly move into the Garden Walkway, as a thought occurs which stimulates reflection. If the coach doesn’t notice and continues as if in the Map Room (“So when did you say you would complete that?”) it may interrupt valuable reflection.

Sometimes we need to coax a client into an appropriate room. A client who continuously undermines their own confidence with a lack of self-belief can be encouraged into the Dark Room to try to discover the root of the self-doubt and determine whether it can be addressed in coaching or needs referral to a therapist or counsellor, for example.

If we have encouraged use of the Dark Room, or the client has entered on their own, how will we know when we’ve spent enough time there? This challenges our intuition and empathy, our capability to question and discern from the answer, or lack of it, whether to stay or to suggest a different space.

If a client shies away from using a particular room, for example, preferring to focus on the practical rather than explore the drivers or blockers impacting on their situation, the coach can let this go or challenge the client to consider a different route.

The moment of decision is a test for both coach and client. A reluctant client may refuse to budge or resist self-insight and the coaching relationship itself may be challenged.

Reflections

The Coaching House offers a framework for reflecting on coaching dilemmas such as those outlined above, for discussion at supervision; for example, remembering a moment when you and your coachee were in different rooms and the resulting disconnect in the conversation.

Questions to ask ourselves may include:

- In which room do I spend most of my time as a coach?

- Can I spot which rooms I avoid?

- In which room do I feel most comfortable? Why?

- In which room do I feel least comfortable? How does that affect my coaching?

- Which rooms do my clients seem to prefer?

With that last question, you might recognise a client who prefers the Play Room, for example, where ideas can be enjoyed without the need to action them, with it morphing into an ‘escape room’, free from responsibility. When the coach recognises this you need to be willing to confront it in the best interest of the client.

Some clients, the butterfly thinkers, flit from room to room, challenging the coach to match the pace, monitor and capture, or challenge progress.

Some clients want to push the coach into the Class Room seeking direction about what to do rather than work it out for themselves. The coach can coax them into another space in which they can take responsibility to explore and to think.

If you’re an internal coach, consider which rooms are most comfortable and which are avoided because of internal pressures or corporate culture, asking, for example:

How can you encourage a senior manager to use the Dark Room and risk revealing thinking they would not wish colleagues to know about?

How do you challenge unethical behaviour in the First Aid Room when you know it’s rooted in the organisational culture?

As you reflect on your coaching, consider how you would configure your Coaching House with different rooms that better reflect how you visualise your contribution to the coaching conversations with your clients.

References

- GROW, first popularised by John Whitmore in 1992 (latest edition, Whitmore, 2017)

- D Hewson and M Carroll, Reflective Practice in Supervision, MoshPit Publishing, 2016

- OSKAR, a solution-focused coaching model developed by Mark McKergow and Paul Z Jackson around the year 2000 (see: https://bit.ly/2V9CaVX)

- J Whitmore, Coaching for Performance: The Principles and Practice of Coaching and Leadership (5th edition), Nicholas Brealey, 2017

- Jeremy Gomm is an independent coach and supervisor and winner of the 2019 Coaching at Work External Coaching/Mentoring Champion Award

- Jan Allon-Smith is an independent coach and supervisor