In the first in a series on team coaching from Ashridge Executive Education, Simon Cavicchia asks: How does Gestalt inform team coaching?

Gestalt philosophy originated in Germany in the early 20th century. Its focus was on how human beings perceived the world.

A significant early discovery was the contextual nature of all perception, whereby something seen becomes figural always in relation to something else, which then becomes background.

Over the years these ideas have been developed and refined to inform relational approaches to psychotherapy, organisational consulting and coaching. Today, the focus of Gestalt psychology is concerned primarily with studying how individuals perceive themselves and the world, how they make sense of these experiences and how this sense-making informs choices and behaviour in ways that either limit or enhance development, effective living, and individual and organisational wellbeing.

In this paper I shall set out a number of core Gestalt orientations, principles and practices and illustrate their implications and applications in the context of team coaching.

Task and process

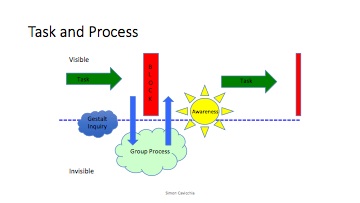

All contemporary theories about teams and team coaching recognise that teams have both a task dimension and a process dimension. Task refers to the function of the team in its context, what its role is as well as the specific tasks and actions it needs to implement moment by moment. Process refers to the human dynamics of the team, the ways in which individuals relate to one another and the wider context in which they are situated, how they feel, think and act together (see Figure 1).

These human system dynamics may not always be visible or easily seen at the conscious level of the team. They may be ‘out of awareness’ but will nonetheless make themselves subtly felt and have the potential to exert a powerful influence on how any team functions in relation to its tasks and situation.

It is often the case when teams encounter difficulties or obstacles impeding effective task execution, that the problem and the solution reside in the territory of team dynamics. Being able to enquire into the team’s group processes can generate awareness and insight in service of moving beyond what might be getting in the way.

Gestalt and teams

Team coaching from a Gestalt perspective offers the opportunity for teams to reflect on the nature of, and relationship between, their tasks and human relationship dynamics. Gestalt shares the humanistic view that individuals and the teams, organisations and societies they co-create are intrinsically orientated towards wholeness, growth and wellbeing.

However, unhelpful patterns can form in teams on the basis of the nature of the individuals who make them up and what this brings to the team, the context in which the team is operating and how individuals respond to these forces, often without being aware of them. The role of the Gestalt-orientated team coach is to observe the ways in which team members organise themselves and their patterns of interaction, and support the establishment of patterns that are more likely to be optimal for the team’s functioning where necessary.

A number of principles support this practice:

Awareness

From a Gestalt perspective, awareness, the ability to notice our feelings, thoughts and the behaviours they give rise to, is key to supporting growth and change. Gestalt sees human experience as a dynamic ongoing process as individuals respond to their needs and to the ever-changing environment they’re situated in. The self, who someone takes themselves to be, how they experience themselves moment by moment, is conceptualised in Gestalt as arising at the boundary between the individual organism and the environment.

Some Gestaltists use the present participle ‘selfing’ to denote the dynamic nature of this process. From a Gestalt team coaching perspective, there is no such thing as a static ‘team’ but an ongoing process or dynamic of ‘teaming’ as individuals organise themselves, feelings, thoughts and behaviours in relation to their tasks, to one another and at the boundary with other teams and the wider context in which they’re situated.

The team coach works to support a team to develop and maintain a capacity for awareness of how it’s organising itself in ways that are effective or less effective in relation to its task and context.

Implications for practice

The team coach will pay close attention to the levels of support and psychological safety in the team and wider context, in order to create conditions where awareness can be cultivated, patterns can be named and team members can become increasingly able to speak their own minds without feeling overly exposed or at risk of shaming one another or being shamed.

While establishing supportive and enabling conditions is extremely important in the early stages of a team forming or of a team coach engaging with a team, the coach will monitor levels of support on an ongoing basis. Every time a team steps to the edge of naming or confronting an issue which may feel challenging or exposing, the coach will attend to how to co-create sufficient support for the team to take the next step, for example, in naming unhelpful behaviour among team members and learning to give direct and honest feedback to one another.

The Gestalt team coach may also model behaviour that is less developed in the team, for example, inviting feedback and giving feedback where this might be necessary. The coach will support the team to pay attention to how members are thinking together and making sense of their situation and challenges in order to reflect on and evaluate how their meaning making might be fit for purpose, creative or limiting in some way. In the case of the latter, the coach will co-create opportunities for thinking differently and experimenting with new perspectives.

As such, creativity and experimentation form a large part of the Gestalt team coach’s repertoire. The coach will co-design exercises and experiments with the team to support the development of required skills in noticing and making meaning from experience. Experiments will be informed by, and arise from, the specific moment-by-moment processes and particulars of the team in its current context.

Field theory – everything is interconnected

How individuals feel, think and act and how teams ‘team’ will be shaped in and out of awareness by the context in which they are situated. The goal of Gestalt is to support healthy and effective living/functioning in the face of shifts in contexts and what these call forth as being optimal responses.

From an existential perspective, responsibility for one’s choices and actions in Gestalt is seen as depending greatly on individual and collective response ability. Change is seen as constant and how individuals, teams and whole systems respond to this constant is a primary focus of Gestalt. This is a particularly useful approach when working in a VUCA world and complex challenging contexts.

Implications for practice

The coach will hold in mind, and be curious with the team in relation to, how events in the wider context are shaping how team members feel, think and choose to act. The coach will name patterns and invite the team to notice and reflect on their experience as individuals and as a team.

Case study

In one team I was working with, which had a strong bias for action, the team would typically structure meetings tightly around delivery priorities and information sharing. Energetically, the climate of the meeting was often characterised by one person presenting in a rather droning and monotone voice with the rest of the team seeming flat and appearing to be entranced by staring at a PowerPoint presentation.

Every now and then a person would ask a question to understand more the context or implications of the presentation for their part of the business. At this point the group would become animated and a lively discussion would ensue, with people sharing different perspectives, reservations, questions. Eventually someone (and it was a different person every time) would say, “hey folks, we are going down a rabbit hole” and the group would return to its trancelike, flat state. As this happened several times, I decided to name what I was seeing.

In a neutral tone I said,“I have noticed that occasionally one of you will interrupt the presentation to ask a question, and the conversation then gets animated. After a short while one of you will say, ‘we are going down a rabbit hole’ and you go back to being quiet and watching the screen. What do you make of this?”

A silence ensued, which often happens when a coach names a pattern that has been out of awareness and takes people to an edge of feeling slightly exposed. Then individuals began to acknowledge that they had noticed it too. They were able to see that when asking questions and talking to each other they felt more energised, but soon they realised they had different views and they began to feel confused, anxious and unsure about how to respond to their differences. They were also able to see that they were in the grip of some powerful beliefs that performance was related to doing things rather than talking about things.

This core belief was driving their behaviour in relation to listing all the activities they were doing as individuals via the medium of presentations. “We are going down a rabbit hole” had become code for “this is all rather interesting but a little overwhelming as we don’t know what to do next so let’s go back to our PowerPoint ritual.”

This was a team that historically had been very poor at acting in a coordinated and consistent way in relation to the team objectives and strategic direction of the business. Together the team and I were able to explore the differences that had fuelled the inconsistent behaviour, explore and understand the different perspectives people had and attend to aligning more overtly. They were able to experiment more with interrupting the passive pattern of listening to PowerPoint presentations and become more active in engaging with one another and the tasks of the team. As a result, their performance and contribution to the wider business improved considerably.

Given the interconnectedness implicit in Field Theory, change in one pattern or aspect will bring about change in other areas of a system, but these cannot be predicted in advance as there will inevitably be a multitude of forces or factors shaping a given moment, set of behaviours or patterns.

Dialogic approach

As in the example above, the coach’s stance is one of being a participant observer. I was able to share that I too felt flat when the team was in thrall to the presentations and became more curious and energised when they began talking to one another.

The coach observes and describes what he/she notices. Interventions are seen as gestures or offers to discover what happens next. The coach pays attention to the response of the team and the meaning they can make from the intervention, if any. In this way meaning, learning and possibilities emerge from the in between of the co-created relationship between the coach and team members. The coach does not pursue a pre-determined agenda other than awareness raising.

Cycle of experience

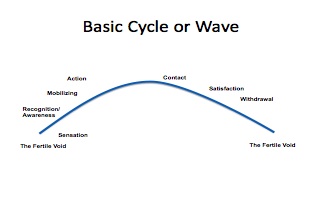

One of the best-known maps of Gestalt theory is the Cycle of Experience. First developed at the Gestalt Institute of Cleveland and refined and adapted since, it seeks to describe the process whereby individuals make sense of their experience and get their needs met by taking action at the boundary between their organism and the environment.

The cycle can also be represented as a wave, as I have done in Figure 2, to denote the ongoing flow of experience from identification of need to the satisfaction once a need has been met.

From a Gestalt perspective we first become aware of a need on the basis of sensation – we feel something.

We then enter the awareness or recognition stage of the cycle where we make meaning from our experience. We might feel a gnawing ache in our stomach and recognise this as a sign of hunger.

In mobilisation, we begin to orientate towards taking action appropriate to our identified need. We may begin to move towards the kitchen and then prepare a sandwich. Contact is where we fully immerse ourselves in the action that is designed to meet our needs, in this case eating the sandwich. Then, having correctly identified the need and taken appropriate action, we enter the stage of satisfaction.

Savouring the sandwich and having allowed our experience to be changed by the action we have taken, we go from feeling hungry to feeling satisfied and nourished. We then enter the stage of withdrawal, where the energy we had invested in meeting the need of hunger is now withdrawn from that task and is free to be invested in whatever next needs attending to. Hunger is an example of a physiological need, but the same process also applies to meeting psychological needs as well as team and organisational tasks.

Given Gestalt’s roots in existential philosophy, which sees human beings as motivated by making sense of experience and finding meaning in their lives, the cycle/wave implicitly offers a map for tracking and paying attention to the process by which this happens.

Notions of health and wellbeing in Gestalt are predicated on being able to move fluidly through each stage of the wave which is then likely to result in appropriate action being taken to resolve the presenting need or issue that an individual or team is facing.

Gestalt pays particular attention to ways in which individuals might inhibit their ability to move through the wave smoothly and thereby limit their potential for a full, vibrant and impactful existence. These inhibiting patterns are referred to as ‘moderations to contact’ and in the context of teams can include:

- Difficulties in sensing and being able to identify needs or form clear foci of attention or ‘figures of interest’.

- Internal messages which might prevent an individual saying what he or she really thinks. In teams this can be as a result of organisational culture and/or team norms which permit and welcome certain patterns of behaviour and discount or punish others. Teams in the grip of norms around politeness and not embarrassing other team members will struggle to give direct developmental feedback, even where this might be vital to ensure the team can deliver against its objectives.

- Lack of support in facing the inevitable disorientation that arises at individual and collective levels when faced with needing to experiment with a way of being or behaving that is new and unfamiliar. This is particularly relevant in the context of teams and organisations developing the agility and innovative orientation needed to respond to unforeseen and hitherto unknown challenges.

Teams and organisations that can be aware of their patterns and reflect on them are implicitly more able to move smoothly through each stage of the wave. This is likely to result in action that is grounded in more of the elements of the context and ensures alignment between team members in relation to action.

A common pattern in many organisations, given the emphasis on doing and taking action, is that teams often move quickly from identifying an issue to action, bypassing the crucial stages of exploration, exploring options and committing to action. This can result in uncoordinated behaviour which is less connected to the richness of information in the field about what action might be optimal. It is more likely to be driven by the different motivations and perspectives of different individuals than any shared understanding.

An added dimension here is that individuals in a team can be in different places on the wave at any one time and so it is necessary to slow down the rush to action to ensure that all team members can arrive at the action phase simultaneously. Otherwise individuals may publicly agree to something in order to move things on but then will not follow through, as privately they may not be at a stage where they can wholeheartedly commit to what has been decided publicly. When this happens it might be construed as resistance to change or doing something new.

From a Gestalt perspective, resistance is viewed as ‘multi-directional energy’ given the different stages individuals might be at. The Gestalt-informed team coach will pay attention to the different energies of individuals and seek to support sufficient alignment for a team to take co-ordinated and committed action where this is required. This includes individuals acting alone with the team’s support. Without alignment, individual activity can easily undermined collective action. These processes and models are particularly useful in helping teams work more effectively in a matrix organisation structure, where individual stakeholders and other teams will also be in different places on the wave.

The role of the coach is to ensure that all stages of the wave are attended to sufficiently to support timely and effective action. This is increasingly important in complex situations where there is a need to unlock the collective intelligence of a team by slowing down to explore different perspectives and strategies for responding to novel and challenging situations.

This process of thinking together and creating new perspectives and possibilities is also key to supporting innovation and creativity adjusting to the complexities of situations teams are increasingly operating in.

- Next issue: team coaching versus team facilitation

- Simon Cavicchia is a Gestalt psychotherapist and supervisor. He is a primary tutor on the MSc in Gestalt Psychotherapy at the Metanoia Institute in London and a faculty member at Ashridge Masters in Executive Coaching. He will be presenting at the 2020 Coaching at Work virtual conference (25-26 November).

- See also Review, page 11

Suggested reading

- S Cavicchia and M Gilbert, The Theory and Practice of Relational Coaching – Complexity, Paradox and Integration, Routledge, 2018

- P Clarkson and S Cavicchia, Gestalt Counselling in Action, SAGE Publications, 2013

- M Fairfield, ‘Gestalt groups revisited: A phenomenological approach’, in Gestalt Review, (8)3, 336-357, 2004

- J B Harris, Field Theory and Group Process, Manchester Gestalt Centre, 1998

- E C Nevis, Organizational Consulting – A Gestalt Approach, Cambridge, MA: Gestalt Institute of Cleveland Press, 1987

Figure 1