Can coaches work ethically and helpfully with clients who are presenting with ‘burn-out’? Tony Geraghty and Adrian Myers report

Have you felt outside of your comfort zone when a client presents with what appears to be ‘burn-out’?

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD; World health Organization: WHO, 2021) describes burn-out as an “occupational phenomenon”. It’s characterised by feelings of exhaustion, job-related negativity and reduced professional efficacy; it’s not classified as a medical condition (WHO, 2019). The challenge in a coaching context is whether a client’s issues as presented, are outside the professional boundaries of the coach.

Many stress-related disorders are classified as medical conditions (ICD, WHO, 2021) and wouldn’t be the legitimate territory of coaching. The NHS (2021) provides advice about how to manage the symptoms and causes of stress ranging from practical advice to the specialist support of health professionals and counsellors.

A recent study has reported that almost half of intensive care unit (ICU) and anaesthetic staff surveyed reported symptoms consistent with a probable diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), severe depression, anxiety, or problem drinking (Mahese, 2021). These are very challenging mental health problems requiring specialist support. In a context of ambiguity, deciding whether to provide coaching or to encourage a client to seek specialist advice and support poses a real dilemma.

The challenge of knowing when to provide coaching is even more challenging given the prevalence of mental health difficulties. MIND (2021) cites evidence of one in four people experiencing some sort of mental health difficulty each year in England, and which one might suppose is likely to be common across the United Kingdom. The British Health and Safety Executive Report states that 828,000 workers suffered from work-related stress, depression or anxiety for the year ending March 2020. Furthermore, 17.9 million working days were lost for these reasons (HSE, 2020).

The first author of this article, supervised by the second author, carried out a study to explore how coaches decide whether they can work with someone seemingly presenting with burn-out and if and how they should work with them.

The researcher used a qualitative methodology using constructivist grounded theory method (Charmaz, 2014). This involved in-depth interviews with six coaches, all of whom had worked with clients they had considered to be showing signs of what they would understand as burn-out.

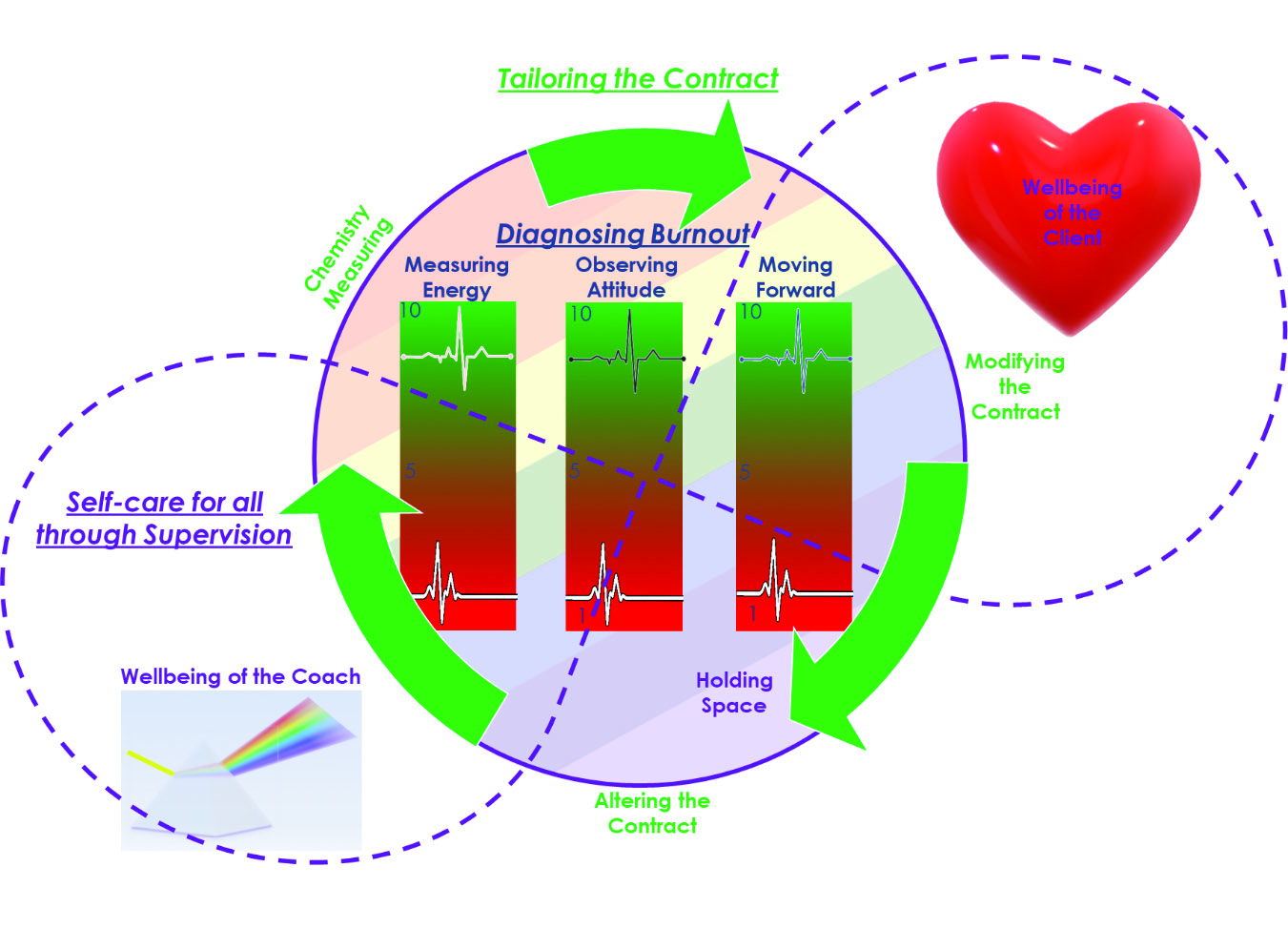

All coaches noticed that their clients showed low energy, work-related negativity (attitude), and lacked capacity to move forward with coaching goals. The coaches usually identified these symptoms in an initial chemistry meeting. These were taken as possible indicators of burn-out and were discussed in supervision.

All participants strongly emphasised the importance of supervision.

Supervision ensured the ongoing assessment of the likelihood of the client’s mental health being more severe than was apparent, or of needing specialist intervention. Supervision ensured that contractual commitments were clearly agreed between coach and client and that they were modified as necessary in order to clarify and formalise how the coach and client would work together to address the client’s experience of burn-out. This enabled the provision of a supportive context while ensuring the coaches didn’t work beyond their skill-set.

Ongoing supervision ensured that supervisor and client gave careful consideration as to whether specialist help was required. Supervision also helped the coaches to attend to self-care given that working with a client whose energy levels were low and whose attitude was often very negative could affect them as coaches.

A coach is expected to be energised, in a positive state of mind and focused on their client for effective coaching (Bachkirova, 2016). It follows that the restorative role of supervision seems important, not only as an end in itself for the coach but it is also in the interests of the client for the coach to be in a positive state of mind. Supervision therefore played an important role in safeguarding the client as well as the coach.

As part of the research, the coaches were asked if WHO’s description of burn-out would be helpful in recognising the symptoms of burn-out. The description was considered to be of considerable help, not only for their own client assessment but also as a framework for discussion in supervision.

Diagnosing mental health difficulties is notoriously difficult, even for trained mental health practitioners (Bachkirova and Baker, 2019). Nevertheless, an opportunity for a sensitising framework to alert a coach to a possible mental health difficulty, seemed to be very important as a basis for personal reflection and an essential topic for discussion in supervision.

The coaches reported that supervision could also help them to reflect on their own capabilities to work with clients and to reflect on tools or approaches they may use. They could discuss what balance might best be established between levels of support and challenge. Finally, they could also discuss with their supervisor how they might broach the issue of a possible referral and how to do this sensitively.

When the coach and client agreed that they were working within the coach’s boundaries, a supportive person-centred style of working with the client often seemed very helpful, including listening attentively to the client and providing a holding environment.

The coaches often asked their clients to rate their progress verbally using a simple scale (1-10) to check in on whether the client was making progress from one session to the next as an indicator of coaching being helpful. This approach seemed to prompt the client to reflect and become aware of his or her own energy levels, attitude towards coaching and ability to move forward.

The main findings are summarised in Figure 1 (below).

Overall, the research raised very interesting questions about the role of a coach, whether a coach can provide a supportive context, and help clients address burn-out while safeguarding both the client and the coach.

The answer seemed to be ‘yes’, provided the coaches discuss the challenges of the clients in ongoing supervision and work within their boundaries and capabilities with

clear contracting while ensuring that the clients’ challenges are not so severe as to need specialist intervention.

About the authors

- Anthony Geraghty is a graduate of the MA in Coaching and Mentoring Practice at Oxford Brookes University.

Email: info@reswellcoaching.co.uk - Dr Adrian Myers is the subject lead for the MA in Coaching and Mentoring Practice at Oxford Brookes University.

Bibliography and further info

- T Bachkirova and S Baker, ‘Revisiting the issue of boundaries between coaching and counselling’, in S Palmer and A Whybrow (eds), Handbook of Coaching Psychology (2nd ed). London: Routledge, 487-499, 2019

- T Bachkirova, ‘The self of the coach: Conceptualization, issues, and opportunities for practitioner development’, in Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 68(2), 143-156, 2016

- D Brennan and L Wildflower, ‘Ethics and coaching’, in E Cox, T Bachkirova and D Clutterbuck (eds), The Complete Handbook of Coaching (3rd ed). London: Sage, pp500-517, 2018

- K Charmaz, Constructing Grounded Theory (2nd ed.) London: Sage, 2014

- R Hawley, ‘Coaching patients’, in C Van Nieuwerburgh (ed), Coaching in Professional Contexts. London: Sage, pp115-129, 2016

- International Classification of Diseases, WHO (2021). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) Version for 2010. Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2010/en#!F43.0

- I Iordanou, R Hawley and C Iordanou, Values and Ethics in Coaching. London: Sage, 2017

- P Jackson and E Cox, ‘Developmental coaching’, in E Cox, T Bachkirova and D Clutterbuck (eds), The Complete Handbook of Coaching (3rd ed). London: Sage, pp215-230, 2018

- M P Leiter and C Maslach, ‘Latent burnout profiles: A new approach to understanding the burnout experience’, in Burnout Research, 3(4), 89-100, 2016

- E Mahese, ‘Covid-19: Many ICU staff in England report symptoms of PTSD, severe depression, or anxiety, study reports’, in BMJ 2021;372:n108. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n108

- C Maslach, W B Schaufeli and M P Leiter, ‘Job burnout’, in Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), pp.397–422, 2021

- Mind, Mental health facts and statistics, 2021. Available from: https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/statistics-and-facts-about-mental-health/how-common-are-mental-health-problems/

- NHS, Stress, 2021. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/stress-anxiety-depression/understanding-stress/

- World Health Organization, Mental Health, Evidence and Research, 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/burn-out/en/

- World Health Organization, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD), 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases

- NHS (2021). How to access mental health resources. Available at:

- https://www.nhs.uk/using-the-nhs/nhs-services/mental-health-services/how-to-access-mental-health-services/

- NHS (2021). Get support from a mental health charity. Available at:

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/stress-anxiety-depression/mental-health-helplines/

- NHS (2021). Every mind matters. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/oneyou/every-mind-matters/

Figure 1: How coaches work with clients with burn-out. (Authors’ own diagram derived from research)