Reverse mentoring can be a win-win relationship in the multi-generational workplace. Ian Browne and Judie Gannon report

Two decades ago, the term ‘reverse mentoring’ started to appear in corporate life.

Popularised by Jack Welch of General Electric, it became known as a way of addressing older leaders’ gaps in knowledge and skills through pairing with junior workers (Chaudhuri & Ghosh, 2012). Adoption by global brands such as Procter & Gamble has seen reverse mentoring deployed in the context of technology and more recently diversity and cultural understanding.

Global trends have fuelled interest in reverse mentoring. Digital connectivity has allowed service businesses to extend rapidly across geographic boundaries. Harnessing and distributing knowledge across organisations has become a critical competency. Younger workers are increasingly qualified in growth areas of computing, data and life sciences, therefore linking expertise with decision-makers at speed has become a source of competitive advantage.

Today’s workplaces are witnessing the first decade with four distinct generations simultaneously active and working together (Harrison, 2016). Although reverse mentoring may have originally been conceived as correcting deficiencies in leaders’ knowledge and cultural understanding (so-called ‘teaching old dogs new tricks’), adoption of the practice has outpaced research and an understanding of how the relationship works (Marcinkus Murphy, 2012). Improving our understanding of reverse mentoring allows HR leaders and others to carefully and confidently deploy the practice and optimise return on investment.

The first author of this article (Browne) supervised by the second author (Gannon) carried out an exploratory study of 10 mentors and mentees using a narrative research methodology of semi-structured interviews to understand the nature of reverse mentoring relationships and how value is generated for both mentee and mentor.

The age gap

Older mentees were drawn intrinsically to reverse mentoring as a means of investing in the next generation. This motivation was sometimes driven by recollections of how they’d been helped in their former career and also observing generational differences within their own family contexts. Mentees were often painfully aware of how culture and hierarchy tended to isolate them from younger and newer entrants, with middle layers of management repackaging raw insight and unformed ideas for more palatable, filtered versions.

Learning as a habit was highly motivating for older leaders. They were strongly aware of horizon issues that weighed deeply and constantly on their minds that weren’t of immediate concern to be resolved in the boardroom, seeking a neutral space within which they could learn through private exploration and reflection.

Younger mentors, often recently out of university, were undoubtedly ambitious to make their mark, yet frustrated at how organisational hierarchy and culture constrained their learning and ability to turn ideas to reality. Challenge and criticality fostered at university were often seen as threatening by teammates and supervisors and new entrants were instead encouraged to learn to fit in and respect their place in the hierarchy, creating significant frustration, and fuelling an intent to leave.

Mentors sought opportunities to step above the organisational silo and see the connected organisation, opportunities to play with ‘big ideas’ of more profound significance and the potential to see the ideas brought to life.

Power imbalance

The potential for reciprocity in the relationship was often tempered by the imbalance of power. Mentors tended to automatically assume a subordinate role, sometimes fearing wider negative consequences of giving critique to their mentee.

Mentor motivation and personal learning objectives were a defining point of difference. Highly motivated mentors tended to take compensatory action to diffuse the power imbalance, increasing trust by exhibiting greater vulnerability. Less motivated mentors, particularly those conscripted by their organisations to take part, tended to sustain the power imbalance, causing anxiety and frustration in the younger mentors. The study showed reverse mentoring to occasionally hold the potential for harm as well as good.

Evolving relationships

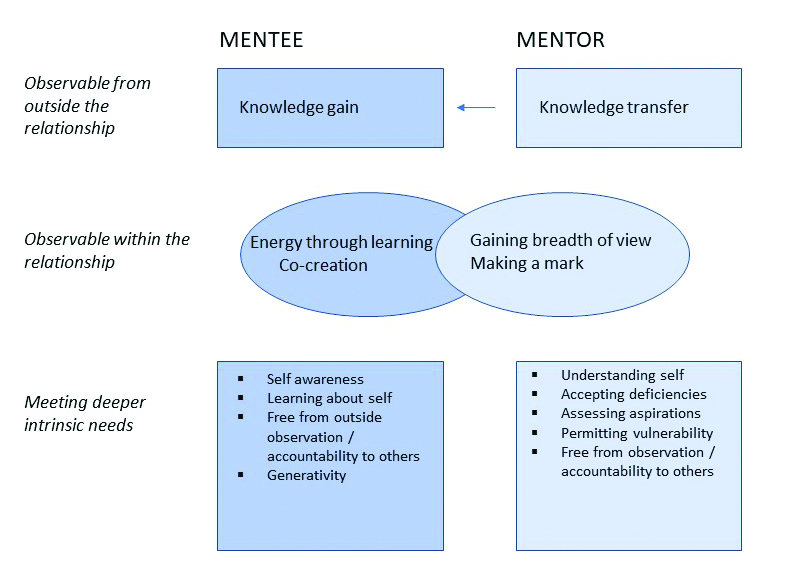

Reverse mentoring, like its traditional cousin, is sustained over time. The study showed contrast in how relationships evolved, characterised in three layers, illustrated in Figure 1.

The first layer, observable outside the relationship, is the commonly understood transfer of knowledge from young to old, valuable yet quickly exhausted.

The second layer, observable between mentor and mentee, contains reciprocal exchanges where learning extends from transferring knowledge to observing and experiencing leadership thinking styles, considerations and constraints.

Mentees enjoy being inspired by raw unconstrained ideas that challenge their thinking. Mentors make connections, learn about the complexity of an organisation’s many moving parts and unspoken rules, accelerating their learning, seeing their ideas shaped for success rather than rejected through critique.

Within the third layer lie yet deeper gains through private and unhurried reflexivity without accountability to or judgement from others, and therefore a rare, intimate and valuable space. Not all relationships in the study achieved this state. Relationships set up to correct a deficit in knowledge tended to work to that self-limiting remit, terminating in a few months as knowledge was exhausted. Mentees choosing a personal, often private objective of crafting this ‘third space’ of learning and development of cultural fluency were most likely to invest in what was necessary to diffuse the imbalance of power and reach deeper available gains.

The research helps HR professionals and others understand that considering reverse mentoring through the lens of teaching old dogs new tricks is self-limiting and fails to recognise the motivational benefits older leaders gain through the act of learning itself. As retirement ages rise, organisations need to consider how to positively harness years of experience in older leaders.

As hierarchical layers flatten, the reciprocal nature of reverse mentoring may become a preferable form of mentoring, allowing younger emerging leaders to accelerate their learning of organisational complexities and achieve intrinsic satisfaction through co-creation. Since satisfaction is linked to affective commitment (Stokes et al, 2013) and talent retention, careful deployment of reverse mentoring creates the ‘win-win’ relationship many multi-generational workplaces can potentially enjoy.

About the authors

- Ian Browne is external skills lead for Lloyds Banking Group

- Dr Judie M Gannon is deputy head of doctoral programmes, subject coordinator – doctorate of coaching & mentoring, and senior lecturer – coaching & mentoring/ human resource management at Oxford Brookes Business School

References

- S Chaudhuri and R Ghosh, ‘Reverse mentoring: A social exchange tool for keeping the boomers engaged and millennials committed’, in Human Resource Development Review, 11(1), 55-76, 2012

- A Harrison, ‘Exploring millennial leadership development: A rapid evidence assessment of information communication technology and reverse mentoring competencies’, in SSRN Electronic Journal, 2016

- W Marcinkus Murphy, ‘Reverse mentoring at work: Fostering cross-generational learning and developing millennial leaders’, in Human Resource Management, 51(4), 549-573, 2012

- P Stokes, P Ghosh, R Satyawadi, J Prasad Joshi and M Shadman, ‘Who stays with you? Factors predicting employees’ intention to stay’, in International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 21(3), 288-312, 2013