This issue we road test: The Project Stress Cycle. Carole Osterweil reports

Have you noticed a trend of anxiety, stress and mental health coming up more often in coaching conversations than they used to?

A recent LinkedIn post from Clare Norman explored the theme, “I notice how many people are in back-to-back calls, with little to no time to rehydrate or use the bathroom … to recalibrate before the next meeting so that their head is in the right space for productive thinking and contributions.

“How have we let this happen? I know, we’re in the end stages of an unprecedented pandemic. But why have so many leaders not figured out the connection between the lack of breaks and the increase in mental health issues? We are not designed to be constantly on, to be at full pelt. We know that the human mind and body cannot take this much punishment.

“We cannot use the pandemic as an excuse – we should have pivoted by now. Not back to normal, but forward to a better way of energy and thinking management,” she said.

In the lively discussion that followed about the causes and implications for coaches, I found one contribution from Frances White, particularly pertinent. It highlighted a “performance obsession” in which, “Phrases like ‘driving for performance’ and large bonuses based on ‘performance’ have contributed to a cultural addiction to constant ‘improvement’ and endless, relentless growth.

“Coaching has sometimes felt like a kind of Botox or performance enhancing drug… Coaching is used to help you ‘perform better’… I find in my supervision practice the same trend. Coaches are also ‘driven’ and feel exhausted, she said.”

White closed her comment with an observation about the parallel process, and an invitation: “It’s the underlying fear culture that you can’t slow down or pause to take a breath, to think. Coaches I think have colluded with this, unwittingly perhaps, as we have also been on the ‘performance’ drive. We should certainly reflect on this.”

Do you agree? Are we coaches colluding with creating this culture?

Her challenge took my breath away. Having reflected on it, my answer is clear. Inadvertently, we are colluding. And this raises another important question, how can we stop colluding?

How can coaches stop colluding with a drive for performance at the expense of mental health?

The clue lies in the closing words of Norman’s post “…even senior managers are fearful of talking to their peers about this, believing they might be seen as shirkers, but I bet everyone will breathe a sigh of relief if someone suggests that you find systemic ways to address the issues.”

In my view, we’ve all fallen into a trap of seeing stress primarily as an individual issue. But focusing on the individual, is often not enough. Increasingly, stress is also a systemic issue. And where it’s systemic, it’ll frequently overpower the good work we do with individuals.

If coaching is going to have long-term impact, we must stop colluding and find ways of drawing attention to the systemic and vicious cycle of excess stress and declining performance.

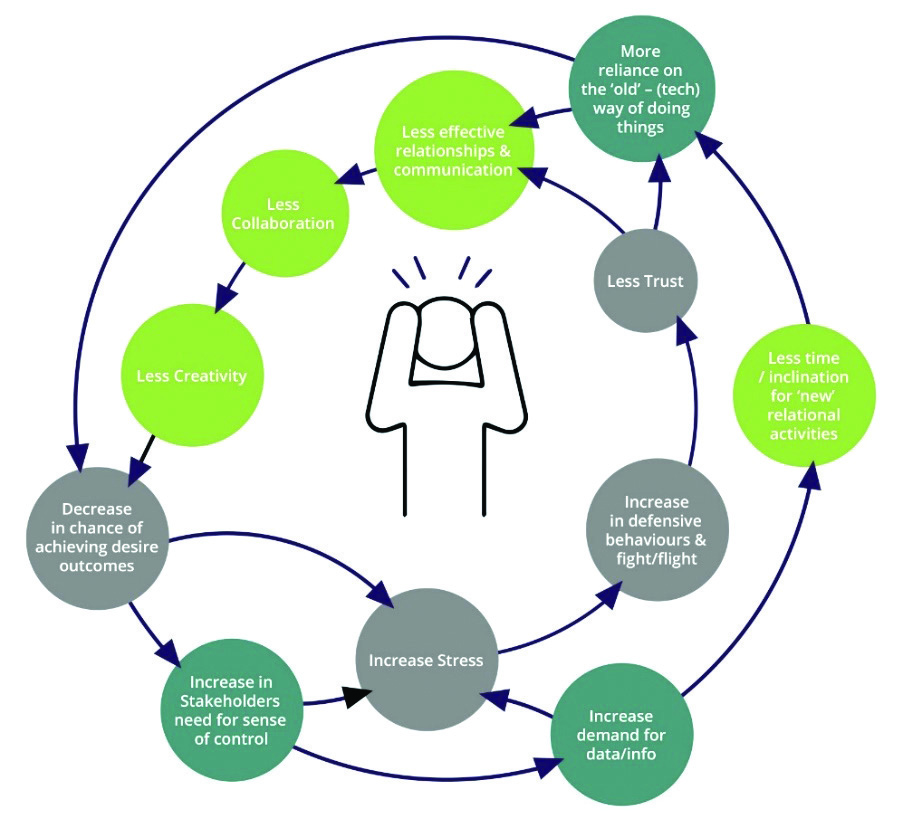

I’ve developed a tool that does this. It’s called the Project Stress Cycle because I first observed this pattern in project management. I’ve since discovered it’s applicable to every corner of life in organisations.

This extract from my book Neuroscience for Projects Success: why people behave as they do (Osterweil, 2022) introduces the cycle, and illustrates how it can be used.

The Project Stress Cycle: Fred

Picture Fred, a senior member of the project team. Things aren’t going his way. He’s getting increasingly frazzled. He’s holding it together but doesn’t realise how stressed he is. He’s snapping at everyone and he’s finding it harder to act in a rational manner.

The impact on those around him is palpable. No one wants to provoke an outburst, so they give him a wide berth. And of course, after a bruising meeting it’s hard to keep your own Thinking brain online. Trust is falling across the piece and relationships and communication are suffering.

When the project started, Fred and his colleagues went out of their way to highlight the need to invest time in building relationships and ensuring people worked well together. They repeatedly reminded the team: “Successful delivery relies on collaboration and creativity”.

But now the pressure is on and metrics are the primary focus. As relationships get strained, collaboration is more difficult. Rather than wasting time struggling to work together, people are falling back into old habits and silos. They’re relying on approaches that worked in the past. But without quality collaboration it’s hard to be creative.

And the word on the street? The project is unlikely to achieve the desired outcomes – which does nothing for stress levels.

Powerful stakeholders are getting nervous. They’re demanding more and more information in slightly different formats to reassure themselves that things are under control. These demands distract the team from the work they should be doing and add to the stress.

They have less time and less inclination to work collaboratively and the preoccupation with spreadsheets and metrics is forcing them to adopt behaviours that reduce the chance of success and multiply stress – right across the system.

The key message is that we need to be alert to excess stress because it can trigger a cycle that plays out across the wider system and impacts delivery. Some organisations slide into stress cycles at crunch points (reporting of quarterly sales figures or year-end financials, for example). Others can be in a chronic state of stress for years.

None of this is surprising, when we consider the powerful stakeholders, the scale of investment and the private and organisational reputations at stake. And it doesn’t stop there.

The story of Fred illustrates how the behaviour of one person generates complexity. Yet it’s a simplification of what happens in real life. In the latter, as soon as we get into team and group environments another source of complexity comes to the fore – our innate need to belong.

When we’re in team and group environments we become sensitive to any indication, real or imagined, that we’ll be ostracised or ejected. This fear, albeit unconscious, also has an impact on the dynamics. It can create a climate of low psychological safety where people are afraid to speak up. Instead, they go along with irrational decisions and dysfunctional behaviour – and this acts as an amplifier.

The quest for high performance can turn toxic

We coaches mustn’t be afraid of speaking about what happens when the quest for high performance is taken to extremes. It creates toxic culture and adversely affects mental health. I’m not exaggerating, in the project world, the research is clear, and I’m sure there are parallels elsewhere.

“We asked about building high-performance project teams and found a recurring theme of brutal cultures and mental health issues. Teams in bigger and more complex projects often have a battle rhythm characterised by cognitive overload, decision fatigue, day-in, day-out conflict and excessive stress. This results in poor mental health or even PTSD like symptoms.”

Collin Smith was summarising the findings of the International Centre for Complex Project Management (ICCPM)’s 2018 Roundtable research into leadership and complex projects. The ICCPM CEO went on: “Unfortunately, there’s a trend: leaders in these projects keep pushing and pushing – to the detriment of their own mental health and that of their teams. And productivity suffers. Yet our research tells us, when complex projects really get tough the opposite is needed.”

We coaches know this. And I’m sure that many of you, like me, have coached leaders like those Smith describes to change behaviour, increase resilience, deal with stress and anxiety differently…the list goes on.

I also suspect that many of us have done this while inadvertently colluding with the ‘performance drive’ White named. It doesn’t have to be like this!

Using the Project Stress Cycle in team and board meetings

We can use the Project Stress Cycle as a starting point to initiate conversations with colleagues and clients about the systemic pattern we might be caught up in. A client of mine, Dan, a programme director working in infrastructure, illustrates its power:

“I’ve often put up a slide of the Project Stress Cycle, in team and board meetings, to kick off a discussion how to recognise the signs of stress, and how to communicate differently. On more than one occasion, immediately after doing this, I’ve got a call from a senior manager. They’ve then told me they were having a similar problem and have asked for a copy of the slide.

“Typically, they’d identified the behaviours in their own teams, but they hadn’t known how to explain it. If they couldn’t explain it, how could they find a solution? The slide enables them to do both. It allows the people who are suffering, in the middle of the diagram, to understand the repercussions of their behaviour – on them personally and on the wider team, without judgement. It also highlights the impact on inter-connections across the whole project.”

As soon as people recognise what’s going on they are keen to start a conversation about how to interrupt the cycle. It’s a safe way to draw attention to systemic patterns without allocating blame, or risking being called a shirker.

TIP

If you suspect there’s a stress cycle at work

- Name it – with the intention of checking out whether others can see all or part of it, too.

- Use Figure 1, or the story of Fred to test the ground.

Figure 1: The Project Stress Cycle Source: Visible Dynamics

© Carole Osterweil, 2022

References

- C Osterweil, Neuroscience for Project Success: why people behave as they do, APM, 2022

- C Osterweil, Project Delivery, Uncertainty and Neuroscience, a Leader’s Guide to Walking in Fog, UK, Visible Dynamics, p25, 2019

- ICCPM and Visible Dynamics, (2020) Stress, Culture and High-Performance Project Teams. https://soundcloud.com/user-680350226/stress_culture_high_performance_project_teams (Accessed 10 June 2021)

- ICCPM International Roundtable Series (2018), Project Leadership: the game-changer in large scale complex projects. https://iccpm.com/project-leadership/ (Accessed 31 July 2019)